Part 2

On a freezing, foggy evening in December, the House of Commons finally formally responded to the last major financial sleaze scandal to hit parliament, and in doing so, sent an important signal about the way politicians look after themselves.

After more than a year of deliberation, the debate and vote late in the evening of Monday 12 December was the moment MPs would finally agree to a package of reforms in the aftermath of the Owen Paterson scandal.

Some might have expected fireworks, given they were collectively responding to the disgrace of one of their own found guilty of lobbying for cash during the pandemic – bringing the stench of political scandal back to Westminster and even hastening Boris Johnson’s departure after the former PM initially stuck up for Paterson.

The votes came shortly after 10.30pm and saw barely half of all MPs shuffling unenthusiastically through the division lobbies to register their position.

I spent much of the evening in central lobby next door and detected little passion or interest about the subject under discussion from all but a handful.

A year earlier, such a vote would have been electric because sleaze was in the headlines, but as the temperatures that night dipped below zero again, it was clear neither MPs nor commentators cared much.

What was agreed that night did amount to an important incremental tightening of the rules that was welcomed by campaigners. But the focus of the Westminster juggernaut had moved on with the change of prime minister. The vote was of little interest because many thought it of minimal practical consequence to them – it might mean up to 30 MPs have to reassess second jobs.

The Labour plan to ban second jobs had no chance of a majority after the Tories backed away earlier in the year. The debate, decision and votes generated not a single headline anywhere. Yet still, this moment sends a fascinating signal.

The real importance of what happened on 12 December 2022 was that MPs were telling the public that, in broad terms, the sleaze safeguards work well as they are. They were ultimately endorsing much of the status quo and deciding it was to stay in place.

The existing system to regulate MPs was, they were saying, fit for purpose and the current transparency declaration rules should stay as they are. And while there is genuine division over banning second jobs between the main parties, there was little sense of a need for other changes.

So what mattered that night was what was not on the table in the Commons and what was not discussed, but so many questions remain.

Is this the best system we could possibly have, given the Paterson affair happened as it did? Have MPs really come up with the best way to collect and publish data about outside earnings, gifts and donations? Is the register of members’ financial interests a sufficient guide to the financial dealings of MPs?

Why shouldn’t we be able to compare MPs’ outside earnings and rank them in order of what they get? Why shouldn’t we be able to work out who are the biggest donors to individual MPs, just as we can for political parties? Why shouldn’t we see more easily the networks donors give to? Who receives the largest sums, and which MPs appear to need no additional donations at all?

Just because there is no apparent appetite amongst MPs to explore these questions does not mean that others should not.

That is why today the Westminster Accounts launches. Built as a collaboration with our partners at Tortoise Media, it marks a major experiment in transparency and public accountability in an attempt to shine a light on how money moves through the political system. And unlike most other exercises in journalism, we are sharing our workings.

In a landmark move, we are publishing a new publicly available tool to give voters the chance to explore. Everyone will be able to play with the financial data we have collected from publicly available sources about each MP, explore a new universe connecting the financial dots across our political universe – and draw their own conclusions.

It is an enormous effort lasting over six months, involving dozens of journalists, data scientists and designers from both media organisations, and is ready to use right now.

The Westminster Accounts in three steps

The Westminster Accounts involves three steps. Firstly, using publicly available data from parliament’s register of members’ interests and the Electoral Commission, Sky News commissioned Tortoise Media to build a spreadsheet showing us data about MPs’ earnings, donations and gifts in this parliament, since December 2019, alongside party donation data from the Electoral Commission database.

We now, for the first time, have a single figure for how much each MP has earned in this parliament and how much has been donated and from where. Alongside this, we have taken the information from the parliament website about the financial benefits provided by private companies and other organisations to fund all-party parliamentary groups that support informal networks of MPs, to help look at business activity in Westminster.

Secondly, Tortoise Media has turned this spreadsheet into a snazzy, carefully curated online tool accessible to everyone via the Sky News website and app. This allows anyone to, in the first instance, search the financial information of any MP and understand their financial affairs in comparison to colleagues.

Then in a powerful and unprecedented move, once users have explored one MP’s financial affairs, they then have the ability to search by donor, MP and party in the political-financial universe represented by a series of globes. This tool will be updated every few weeks with the latest data provided by the authorities, at least up until the next general election.

Thirdly, the data has been studied, collected and used to tell a series of interesting stories both about what we discovered and what the numbers reveal – but also about where the transparency promised by our leaders falls short.

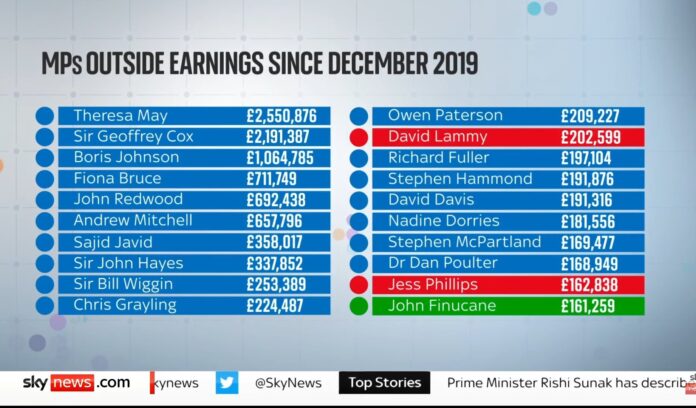

Today we look at second jobs data, publishing a league table of the highest earners since December 2019, a feat not possible until now. But by treating the data as a starting point for our enquiries, we go deeper by examining company accounts of leading politicians and comparing second job promises with reality.

The significance of the stories in the coming days will be the discovery of what politicians have not told us, as well as what they have.

Risks of the project

This project is not without risk. We have created league tables of donors and earners, something the political system disliked. We will be told we have ignored context – some earnings are donated to charity, some MPs will earn more than others for less work, and MPs in marginal seats will have to raise more funds for campaigning than those in safe seats.

But we defend our right to look at the numbers in this way; and encourage the conversation that will follow, however difficult.

The most complex task, in crude terms, has been to turn the register of members’ interests into a spreadsheet. This involved turning the register’s complex written entries into stark figures for spreadsheet cells, stripped of the context which appears in their preferred format to allow us and our viewers to compare like with like. MPs will inevitably object, assert the project unfair and hunt for discrepancies.

This is not a process that – yet – can be done automatically and has involved hundreds of person-hours to check and double-check the entries. Given the volume of data on that scale, human error is an inevitability, and we will correct those and listen carefully to complaints.

However, we have assembled the data based on information MPs are required to submit, based on a methodology which has been externally validated and is available on this website. We profoundly believe and would justify our right to attempt such an exercise, to compare and contrast MPs – something by their nature they often feel uncomfortable about.

But rather than avoiding the exercise, Sky News is attempting to help shine a light on how money works in politics, so the public better understands what is going on.

If MPs are to defend what they believe are reasonable, legitimate practices, explaining them clearly rather than hiding them away might be a better answer.

Hannah White, director of the Institute for Government, goes further, suggesting it would have been entirely possible for MPs to do what we have – but avoided this for a reason.

“I think it’s a really good question why parliament hasn’t done this before for itself and the answer really is hiding in plain sight. There’s no incentive. For MPs really to make it easy to do the sort of comparison that you’ve done in this exercise.

“It’s much easier for them to say we’ve been transparent data is out there. People can go and look for it if they want to. But in fact, that data isn’t very easy to use, and it’s not real transparency.”

“I think the value of this tool is it enables us to see what real transparency might look like and hopefully, parliament and the Electoral

Commission, will reflect and think, are we actually achieving the end that we’re trying to achieve? When we require transparency from our politicians, from our political parties, should we be doing this better ourselves? Should it be up to Sky and Tortoise to be doing this data analysis?”

Transparency is the best disinfectant

After every Westminster scandal, we are told that “transparency is the best disinfectant”. That is what we are testing in this exercise, and looking at the information they are required to submit to evaluate what it tells us.

We started from an important set of principles. There is no assumption money in politics is a bad thing, just a political reality. This project has not set out to find a scandal and nor have we stumbled across one.

We make no judgement on MPs’ holding second jobs or getting money from outside sources, just defend our right to try and compare MPs with each other on the basis of their earnings. (We note Sir Geoffrey Cox, who is happy to provide a lengthy explanation of his barrister work, was elected by the voters of West Devon and Torridge with healthy majorities at each of the last five general elections.)

Our only goal has been to understand better what goes on as money flows through the system.

But as viewers will see from our reporting this week, that transparency has felt like it too often falls short, and when MPs are asked questions about donations, earnings, donors or gifts, they shy away from the camera and try and ignore the questions. Far too often evasion is the default response when questions involve money.

Politicians always tell us that we can trust them because they are transparent – that they are upfront about all of their dealings.

Last month MPs quietly made clear they were broadly content with the level of transparency the public is offered, tinkering with rather than transforming the system. This week the Westminster Accounts will pose the question of whether the rest of us are too.