In popular discourse and political debate, terms like “socialism” and “communism” are often thrown around to describe states like the former Soviet Union, China, or Cuba (and ever increasingly by those on the far right at anyone who disagrees with them). However, from a strict classical Marxist perspective, this is a fundamental misreading of theory. Marxism argues that not only has a genuine communist society never been achieved, but the very concept of a “communist state” is a contradiction in terms. The journey from capitalism to communism is a protracted, transformative process, and what we have witnessed in history are, at best, unsuccessful attempts to begin this journey.

The Marxist Blueprint: A Society’s Evolution

To understand this, we must first grasp the Marxist view of historical progression. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels posited that human society evolves through distinct stages, defined by their mode of production (how goods are produced and who owns the means of production):

- Primitive Communism (tribal society)

- Slave Society

- Feudalism

- Capitalism

- Socialism (a transitional phase)

- Communism (the end goal)

The transition from one stage to the next is driven by class struggle. Under capitalism, this is the struggle between the bourgeoisie (the owning class who suck up the wealth and power and control much of what we do) and the proletariat (the working class who are ripped off and divided via multiple strategies). Marx believed this conflict would inevitably lead to a revolution once the working class realised what the bourgeoisie were doing to them.

The Dictatorship of the Proletariat: The Transitional State

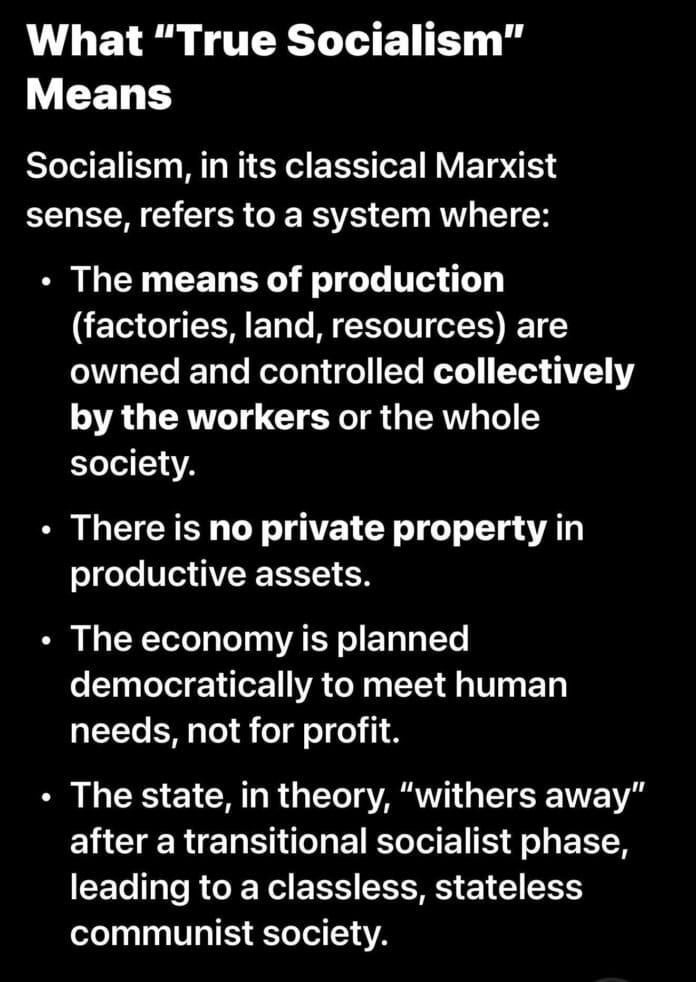

This is where the crucial, and often misunderstood, transitional phase begins. After the overthrow of the capitalist class, society does not immediately leap into communism. Instead, it enters a preliminary stage sometimes called socialism, or what Marx termed the “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

It is vital to clarify this term. For Marx, it did not necessarily mean a brutal, autocratic rule by a single party (though that is how it materialised in the 20th century). Rather, it meant a state where political power was held by and for the working class, as opposed to the “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie” he saw in capitalist ‘democracies’.

The primary purpose of this state is twofold:

- To suppress the resistance of the former ruling class: To prevent the bourgeoisie from reclaiming power.

- To socialise the means of production: To gradually bring land, factories, and resources under collective social ownership.

Crucially, this transitional state is still a state. It possesses the classic features of a state apparatus: a government, police, courts, and a standing army. It exists because class antagonisms have not yet fully disappeared.

The “Withering Away of the State”: The Core of the Process

Here lies the central thesis of the Marxist argument. This proletarian state is not meant to be permanent. Its very existence is a necessary but temporary evil. As the resistance of the old ruling class is broken and the new, socialist economic relations become entrenched, the need for a repressive state organ begins to diminish.

Engels famously described this process as the state “withering away.” It does not mean the state is abolished overnight by revolutionaries. Instead, it gradually becomes superfluous as class distinctions dissolve. When there is no longer a ruling class to suppress a subordinate class, the state, as an instrument of class rule, loses its function. It is replaced by the “administration of things” and the “direction of production processes” – a technical, cooperative management of society without the need for coercive power.

This is the point where the higher phase, communism, is achieved. A communist society is stateless, classless, and moneyless. It operates on the principle, “From each according to ‘his’ ability, to each according to ‘his’ needs (‘their’ needs now”). The coercive apparatus of the state has withered away, leaving a free association of producers.

Why the Soviet Union, China, etc., Were Not Communist

From this analytical framework, we can see why a Marxist purist would argue that the so-called “communist states” of the 20th century never reached their stated goal.

- They Never Withered Away: The most glaring divergence is that these states did not wither away. Instead, they grew into immensely powerful, centralised, and often brutally repressive bureaucracies. The state apparatus, rather than dissolving, became an end in itself, with a new bureaucratic class (what some critics called a “state bourgeoisie”) emerging.

- The State Became Permanent: These regimes became stuck in the “dictatorship of the proletariat” phase, or more accurately, a distortion of it. The state became a permanent fixture, controlling every aspect of life, rather than a temporary instrument on the path to its own obsolescence.

- Existence of Class and Inequality: While they abolished private capitalism, new forms of social stratification and privilege based on party membership and state power emerged. A genuine classless society was not realised.

In essence, these historical experiments are better understood, from a Marxist lens, as state-capitalist or bureaucratically deformed workers’ states. They socialised property, but they failed utterly in the ultimate Marxist objective: creating the conditions for the state to disappear.

Read more:

A Journey Interrupted

The Marxist vision of communism is a radical, long-term historical project. It is not an event but a process, the culmination of which is a stateless and harmonious society. The historical attempts to build communism, while inspired by Marxist critique, became trapped in their initial, authoritarian phase. They demonstrated the immense difficulty of managing a transition away from capitalism and, critics would argue, highlighted a potential flaw in the theory itself: that a powerful state, once created, has a tendency to entrench its own power rather than voluntarily relinquish it.

Therefore, to claim that communism has been tried and failed is, from this analytical standpoint, inaccurate. What has been tried is a particular, often authoritarian, form of state-led transition—a journey towards communism that, according to its own theoretical map, never came close to being completed. The ultimate destination, a stateless communist society, remains a theoretical proposition, one that has yet to be realised in history.

And remember Marx’s own words initially spoken in French following the distortion of his ideas during his lifetime:

“Ce qu’il y a de certain, c’est que moi, je ne suis pas marxiste”.

“If one thing is certain, I am not a Marxist”.

As the French philosopher Roland Barthes said when observing how each person distorts the original narrative:

“The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.”