People the world over should breathe this in and be set free.

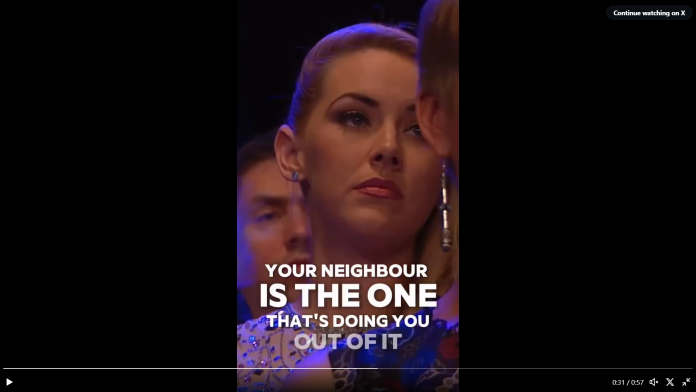

most days I’m convinced this is the greatest moment in irish tv pic.twitter.com/fUVYxGWILB

— Irish Unity 🇮🇪🇵🇸 (@IrishUnity) October 8, 2024

How It Works

In modern societies, a recurring narrative suggests that the working class is held responsible for societal failures while the wealthy elite largely evade accountability. This cycle of blame is entrenched in economic systems, political discourse, and cultural narratives, perpetuating inequalities and hindering social mobility. From policies that favour the affluent to media depictions that vilify the poor, the working class finds itself trapped in a system designed to maintain the status quo.

The origins of this dynamic can be traced back to the birth of industrial capitalism. As Karl Marx observed in Das Kapital, the capitalist system relies on the exploitation of the working class to generate wealth for the ruling elite. The division between the bourgeoisie, who control the means of production, and the proletariat, who sell their labour, is fundamental to the economic inequalities inherent in capitalism. The ruling class not only benefits from this arrangement but also manipulates it to maintain their position of power. By controlling political and legal systems, the wealthy ensure that policies are enacted which reinforce their dominance, often at the expense of the working class.

In modern times, neoliberal economic policies have further exacerbated this divide. The deregulation of markets, privatisation of public services, and weakening of trade unions have all contributed to the erosion of workers’ rights and living standards. Wealth has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a small elite, while wages for the majority have stagnated. Yet, when economic crises occur, it is often the working class who are blamed. The 2008 financial crash, for example, was caused by the reckless behaviour of major financial institutions, yet the subsequent austerity measures disproportionately affected the poor. Public sector cuts, wage freezes, and benefit reductions were justified as necessary to reduce the deficit, even though the crisis itself was a result of irresponsible banking practices and lax financial regulation.

As the economist Joseph Stiglitz remarked, “Austerity is a way of getting those who had nothing to do with the crisis to pay for it.” In the UK, the Conservative government under David Cameron and George Osborne implemented a stringent austerity programme following the crash, reducing public spending on essential services such as healthcare, education, and social welfare. These cuts disproportionately impacted low-income families, while the wealthy were largely shielded from the effects. Moreover, the narrative that austerity was necessary to reduce government debt ignored the fact that the financial sector, not ordinary workers, was responsible for the crisis in the first place. The blame was shifted from bankers to benefit recipients, and the working class was once again scapegoated for a problem it did not cause.

The media plays a crucial role in perpetuating these narratives. In Britain, the portrayal of the working class in tabloids and television often focuses on negative stereotypes. Shows like Benefits Street and Jeremy Kyle depict working-class individuals as lazy, irresponsible, and dependent on welfare, reinforcing the idea that poverty is a result of personal failings rather than systemic inequality. This type of programming not only entertains but also subtly reinforces the notion that the working class is to blame for its own predicament. By focusing on individual cases of supposed moral failure, the media diverts attention from the broader economic and political structures that perpetuate inequality.

This process of “othering” the working class creates a convenient scapegoat for societal problems. Politicians and the media frequently invoke the concept of the “undeserving poor” to justify policies that disproportionately harm low-income individuals. For example, during the 2010s, the UK government implemented stringent welfare reforms that targeted benefit fraud, despite the fact that such fraud accounted for a tiny fraction of overall public spending. The perception of widespread abuse of the system was fuelled by media stories focusing on extreme cases of fraud or irresponsible spending, painting the entire working class as dishonest or undeserving. In reality, many benefit claimants were victims of broader economic forces, such as unemployment and low wages, rather than individual failures.

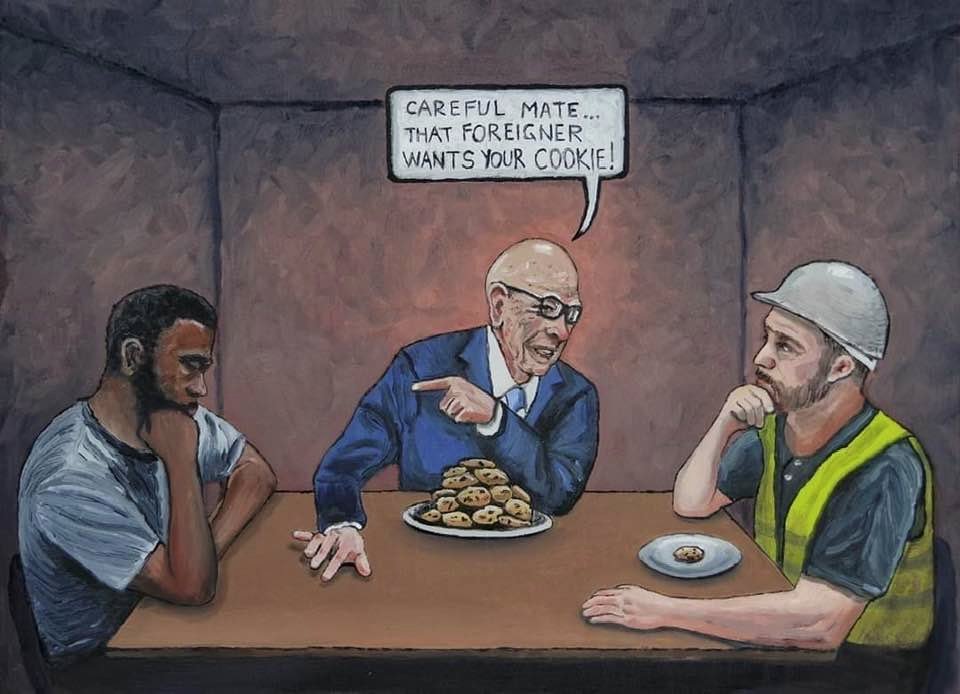

At the same time, the wealthy elite are rarely subjected to the same level of scrutiny. Corporate tax avoidance, for instance, costs the UK billions of pounds each year, yet it receives far less attention than benefit fraud. Companies like Amazon, Google, and Starbucks have been criticised for paying little or no tax in Britain, but the political will to address this issue has been weak. Instead, the focus remains on cutting public spending and reforming welfare, further disadvantaging the working class. The double standard is glaring: while the poor are vilified for relatively minor infractions, the rich are able to exploit loopholes in the system without facing significant consequences.

The myth of meritocracy is another tool used to maintain the status quo. In theory, meritocracy is the idea that individuals can succeed based on their talents and hard work, regardless of their social background. In practice, however, the opportunities available to the wealthy and the working class are vastly different. Access to quality education, professional networks, and financial resources gives the children of the wealthy a significant advantage in life. Despite this, the narrative persists that success is solely a result of individual effort. Those who do not succeed are therefore deemed to have failed because of personal shortcomings rather than systemic barriers. This myth serves to justify existing inequalities, as it implies that the wealthy are deserving of their success, while the poor have only themselves to blame.

Education is a key battleground in this struggle. In the UK, the disparity between private and state education is stark. Elite private schools such as Eton, Harrow, and Westminster charge exorbitant fees and offer a level of education and extracurricular opportunities that are simply unattainable for the vast majority of working-class families. The old boys’ network, where graduates of these schools go on to attend prestigious universities like Oxford and Cambridge before securing high-powered jobs in politics, law, and finance, further entrenches class divisions. As George Monbiot has noted, “The purpose of the education system is not to promote equality, but to sustain inequality.”

The lack of investment in state education has also contributed to the perpetuation of inequality. In recent years, cuts to school funding have led to larger class sizes, fewer resources, and a decline in extracurricular activities. Working-class children are therefore at a disadvantage from the outset, and this disadvantage is compounded by the rising cost of higher education. The introduction of tuition fees in the UK in the late 1990s and their subsequent increase to £9,000 per year in 2012 has made university education increasingly inaccessible for low-income families. While wealthy students can rely on parental support, working-class students are often forced to take on significant debt or forgo higher education altogether.

The labour market further reinforces these inequalities. Insecure, low-paid jobs have become increasingly common in the UK, particularly in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The rise of zero-hours contracts, gig economy jobs, and part-time work has left many workers struggling to make ends meet. These jobs often lack benefits such as sick pay, holiday pay, and pensions, leaving workers vulnerable to exploitation. Meanwhile, executive pay has soared, with CEOs of major companies earning hundreds of times more than their average employees. Despite this, there is a persistent narrative that the working class is lazy or unproductive, while the wealthy are portrayed as hardworking and deserving of their success.

In reality, the economic system is structured to favour the wealthy at the expense of the working class. The economist Thomas Piketty has shown in his landmark work Capital in the Twenty-First Century that wealth inequality is not a result of individual effort but of systemic factors such as inheritance, capital gains, and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. Piketty argues that without significant intervention, inequality will continue to grow, with devastating consequences for social cohesion and democracy.

This growing inequality has also had political ramifications. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of populism in both Europe and the United States, with politicians such as Donald Trump and Nigel Farage capitalising on the disillusionment of working-class voters. These politicians often blame immigrants, minorities, and the “liberal elite” for the problems facing working-class communities, diverting attention from the role of the wealthy in perpetuating inequality. This tactic of divide and conquer has long been used by the ruling class to prevent solidarity among the working class. By pitting different groups against each other, the wealthy are able to maintain their grip on power.

The Brexit referendum in 2016 is a prime example of how the working class is manipulated for political ends. Many working-class voters supported Brexit because they believed it would lead to greater control over immigration and improve their economic prospects. However, the reality is that the economic policies of the British government, not the European Union, were largely responsible for the decline of manufacturing jobs and the rise of insecure work. Instead of addressing these issues, politicians like Boris Johnson and Michael Gove used the referendum to distract from the real causes of inequality, while advancing an agenda that ultimately benefited the wealthy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the disparities between the working class and the wealthy. While many white-collar workers were able to work from home during lockdowns, key workers in sectors such as healthcare, retail, and delivery services were forced to continue working in unsafe conditions, often for low pay. The government’s initial reluctance to provide adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) for NHS workers, combined with the poor pay and treatment of essential workers, revealed the extent to which the working class is undervalued. Meanwhile, companies such as Amazon and Tesco saw their profits soar during the pandemic, yet many of their workers continued to be paid low wages with little job security.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, it is likely that the working class will once again be made to bear the brunt of the economic fallout. Governments have already begun discussing austerity measures to address the rising levels of national debt, despite the fact that such policies have been shown to disproportionately harm the poorest in society. The wealthy, on the other hand, are likely to emerge from the crisis relatively unscathed, thanks to their financial resources and political influence.

Thus, the working class is systematically kept in its place and blamed for problems that are the result of policies and practices designed to benefit the wealthy. From the exploitation of labour under capitalism to the scapegoating of the poor in times of economic crisis, the wealthy elite have consistently manipulated the system to maintain their power and privilege. Through political, economic, and cultural means, the working class is vilified, marginalised, and denied the opportunities necessary to achieve social mobility. Until these structural inequalities are addressed, the cycle of blame and exploitation will continue, with the working class bearing the burden of societal failures while the wealthy remain insulated from accountability.

KEEP US ALIVE and join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg AND SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/