Tom Hurndall was not a soldier. He did not carry a weapon, nor did he wear a flak jacket marked with the power of any nation. He carried a camera and a conscience. He walked unarmed into one of the most dangerous places on earth, not because he sought glory, but because he believed, with a rare and uncompromising clarity, that the lives of children under fire mattered more than his own safety.

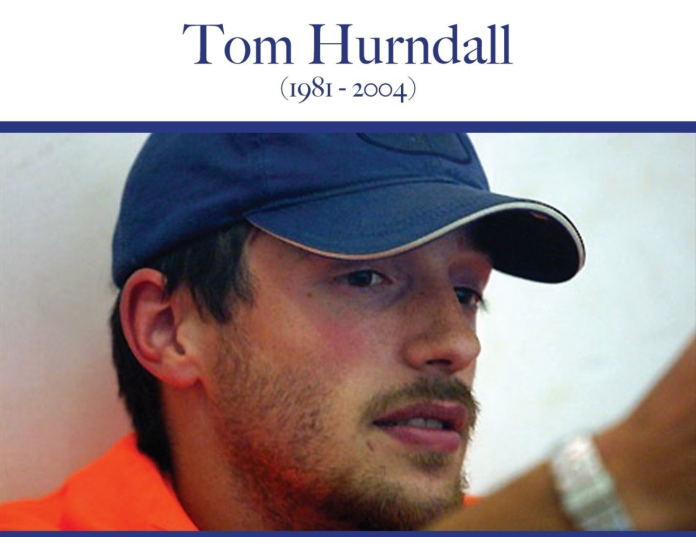

Born in Manchester in 1981, Tom was, by all accounts, a young man driven by empathy and a deep-rooted sense of justice. He studied photography at Manchester Metropolitan University, driven by a desire not only to capture images but to expose truths. He wasn’t content with passive observation; he wanted to stand alongside the people whose stories he told, even if it meant putting himself in harm’s way.

In early 2003, while most of his peers were immersed in student life, Tom joined the International Solidarity Movement and travelled to Gaza, a strip of land suffocating under blockade and military occupation. Gaza was a place where lives were measured in gunshots and headlines barely scratched the surface of daily horror. Tom’s mission was clear: to use his lens and his presence to document abuses and protect civilians wherever he could.

On 11 April 2003, in Rafah, southern Gaza, Tom spotted a group of terrified children pinned down by gunfire. Without hesitation, he stepped forward to shield them, waving for them to run to safety. He never made it. An Israeli sniper took aim and fired a bullet into his head. Tom was left to bleed in the dirt, a brutal reminder of how cheaply life can be valued in a war zone.

He lay in a coma for nine months before dying in a London hospital on 13 January 2004, aged just 22. His death was not collateral damage. It was a targeted act, an effort to silence a witness. But Tom’s story did not end with his final breath.

His family, unwilling to accept silence or whitewash, fought tirelessly for accountability. They refused to let Tom’s death be buried beneath diplomatic evasions. Their campaign forced an Israeli military trial, an almost unprecedented event. The soldier who killed Tom, Taysir Hayb, was eventually convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to eight years in prison. Many would argue that justice, if it came at all, was partial and painfully insufficient.

Tom Hurndall’s killing exposed not just the deadly risks faced by unarmed activists in conflict zones but also the impunity with which violence against civilians and observers is too often carried out. He became, unwillingly, a symbol of the price paid by those who dare to bear witness to oppression.

His death also raised uncomfortable questions about Western complicity and the selective outrage of international politics. Would his story have been told at all if he had not been British? If his parents had not fought so relentlessly? If the camera in his hands had not captured the bleak realities that many would rather ignore?

Tom’s legacy is not just a foundation in his name or a few fleeting headlines. It is a challenge to journalists, to activists, to ordinary people, to refuse silence in the face of injustice. His life is a reminder that bearing witness is not a passive act. It is dangerous. It is defiant. And it is necessary.

In the end, Tom Hurndall gave everything for that belief. His courage continues to echo far beyond the streets of Rafah, in every image taken to hold power to account, in every voice raised against injustice, and in every moment someone chooses to stand between violence and the vulnerable.