If British politics were a reality TV show, the current implosion of the Conservatives and Reform UK would resemble The Traitors stripped of all suspense, wit and guilty pleasure. Just endless suspicion, backstabbing and contestants loudly accusing one another of being frauds – often with some justification. The sacking of Robert Jenrick and his defection to Reform UK have merely dragged this farce into the open.

It is worth pausing to reflect on the extraordinary political journey Robert Jenrick would have had to complete for any defection to Reform UK to appear even remotely plausible. He first entered Parliament in a 2014 by-election where his principal rival was Nigel Farage’s then party, UKIP. From the outset, Jenrick was no insurgent populist: he was a polished, mainstream Conservative, very much of the Cameron–Osborne mould.

Once in the Commons, he voted to remain in the European Union and, after the referendum, backed Michael Gove and then Theresa May in the subsequent leadership contest. This was not the CV of a future Reform UK firebrand but of a conventional Tory moderniser. Under May, he was rewarded with a junior Treasury role, cementing his status as a safe pair of hands rather than a culture warrior.

His decisive pivot came in 2019, when he joined Rishi Sunak and Oliver Dowden in endorsing Boris Johnson’s leadership bid. At the time, this was seen as a crucial signal that momentum among ambitious Conservative rising stars was swinging behind Johnson. Of the trio, Jenrick emerged with the biggest prize: housing secretary in Johnson’s first cabinet.

Yet his ascent stalled almost as quickly as it began. While Sunak and Dowden continued their upward trajectories, Jenrick drifted. When Sunak eventually became prime minister, Dowden was elevated to one of his most trusted lieutenants and ultimately deputy prime minister. Jenrick, by contrast, found himself relegated to immigration minister – not a full cabinet role, and a far cry from the power he once enjoyed.

Friends say it was this job that changed him. Confronted with what he regarded as a deeply dysfunctional immigration system, Jenrick hardened his views. Critics inside his own party were less charitable, arguing that his sudden shift to the right looked suspiciously like political opportunism from someone positioning himself for a post-election leadership contest.

That tension finally snapped when Jenrick resigned, declaring that Sunak’s policies on illegal immigration did not go far enough. From that point on, his rightward drift accelerated, not just on borders but across a range of cultural and political issues. It was this trajectory that led Kemi Badenoch to conclude he was on the brink of making the ultimate leap – and to sack him, plunging the Conservative Party into yet another bout of public chaos.

The Liberal Democrats were quick to mock the spectacle, suggesting Badenoch’s move “makes The Traitors’ roundtable look united”. A party source piled in, remarking that “the country deserves better than a clapped-out Labour government and the same old Conservative chaos”. It was a line dripping with cynicism, but also one that captured the weary mood of the electorate.

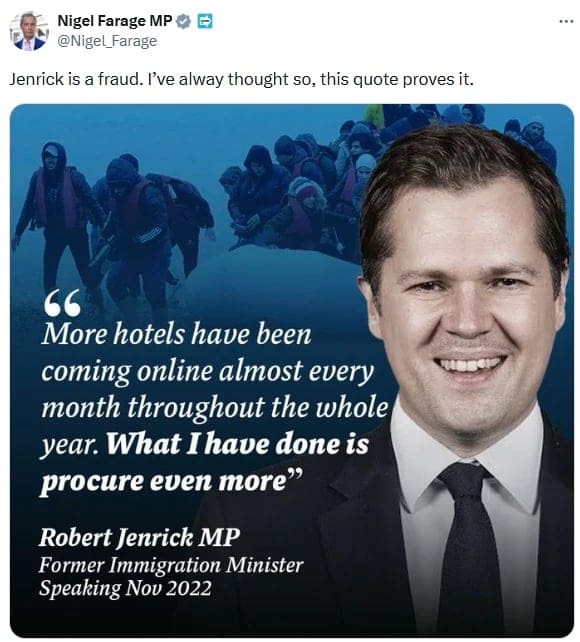

What makes the whole saga darkerly comic is the history between Jenrick and Reform UK. As recently as August, Nigel Farage was publicly denouncing him. Posting on X, Farage wrote: “Jenrick is a fraud. I’ve always thought so,” helpfully underlining his contempt with a misspelling for good measure. This is not ancient history quietly forgotten; it is part of the very recent political record.

Nor was Farage alone. Last week, Laila Cunningham, unveiled amid great fanfare as Reform’s London mayoral candidate, said she did not want Jenrick anywhere near the party, accusing him of having “allowed migrant hotels to flourish” during his time as immigration minister. Meanwhile Zia Yusuf, Reform’s head of policy and former chairman, has spent years attacking Jenrick’s record with relish. If Jenrick were ever to defect, Reform would have to perform some truly heroic mental gymnastics to explain why yesterday’s “fraud” had suddenly become today’s convert.

And this is where the analogy with The Traitors really bites. In that show, contestants at least pretend to seek truth and unity, even as they sharpen the knives. In the Tory–Reform ecosystem, the knives are already bloodied, and nobody is even pretending anymore. Accusations fly, loyalties dissolve, and yesterday’s enemies are tomorrow’s allies – until the next round of betrayal.

What the episode lacks, however, is entertainment. There is no clever twist, no charismatic host, and no sense that anything meaningful is being decided. Just a tired political class circling itself, hurling accusations of fraud, opportunism and chaos – accusations that, uncomfortably for all involved, often ring true.

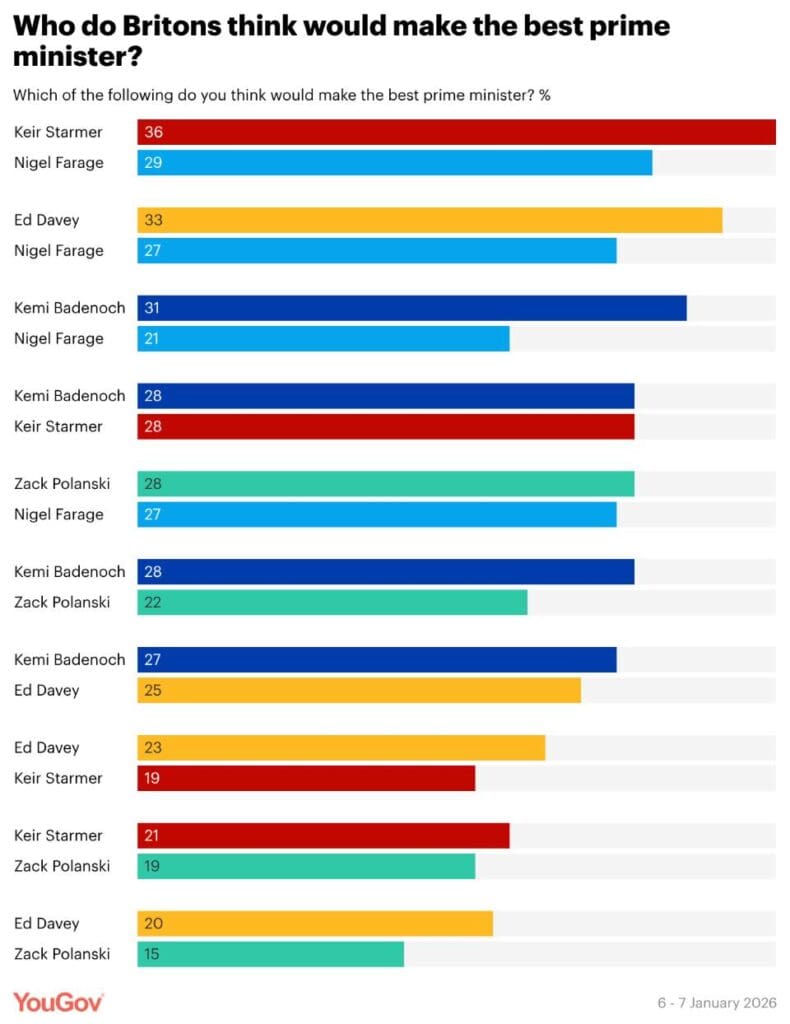

Public Do Not Want Farage

This chart shows that Nigel Farage consistently loses head-to-head match-ups against every other named political figure. Whether he is compared with Keir Starmer, Ed Davey, Kemi Badenoch, or Zack Polanski, Farage never comes out on top. Even when his score is relatively high, it is still lower than his opponent’s, which is crucial: these are not abstract approval ratings but direct choices about who would make the better prime minister. Repeatedly, the public picks someone else.

More striking is the breadth of that rejection. Farage is beaten by leaders from across the political spectrum: Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat and Green-aligned figures all outperform him. This undermines the idea that his appeal is limited only by party loyalty or tribal politics. When voters are asked to make a simple judgement about competence for the top job, Farage’s support plateaus in the low-to-high 20s, while his rivals regularly reach the high 20s or mid-30s. That suggests a hard ceiling on his credibility rather than a temporary dip.

Finally, the pattern reveals a deeper problem for Farage: familiarity does not translate into trust. He is one of the most recognisable political figures in Britain, yet recognition alone is not enough to persuade voters he should run the country. The public may enjoy his insurgent rhetoric or media presence, but this data shows they do not want him as prime minister. In short, Farage is visible, vocal and polarising — but when it comes to governing, the electorate consistently chooses someone else.