As part of Banned Books Week 2025, we are publishing an article a day. Banning books is part of the authoritarian ideology to deprive children of the capacity to think independently in case they think differently from those who seek to control them.

Today we focus on a book on the GCSE English syllabus that has been challenged by those who adhere to right-wing ideologies who seek to suppress and patronise young people.

Reading Assignment

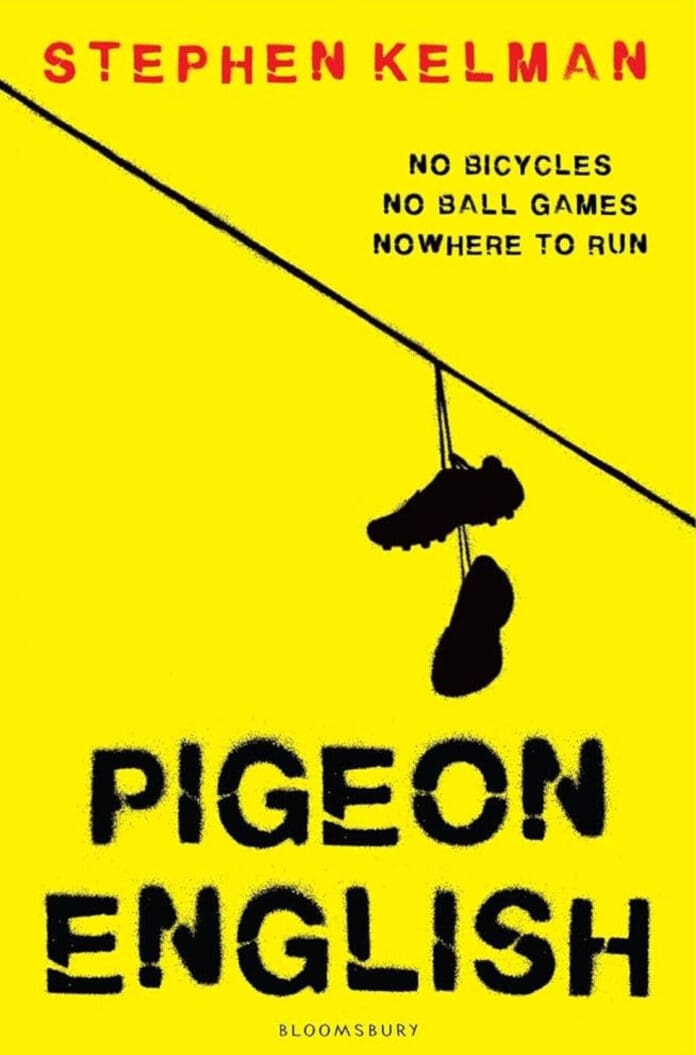

Book: Pigeon English

Author: Stephen Kelman

Student: Eddie Snide

Age: 14 ½

Since this project is about ‘Banned Books’, and in view of a story that’s been dominating the local media in recent weeks,

let’s begin by addressing the [conspicuously white] elephant in the room: the arguments for stopping this book from being recognised as approved for reading in schools or included in the GCSE curriculum.

First of all, we need to clarify what this book is: it is the story of an 11-year-old Ghanian boy called Harrison Opoku – Harri to his friends – told mostly in his own words and his own voice, apart from occasional interjections from a philosophical pigeon, who does not appear to have a name. Presumably because she’s a pigeon. Harri has just arrived in England with his mother and older sister and is living with them in a tower block in south-west London, having left his father behind to sort things out in the village in Ghana where Harri has lived all his life until very recently.

Harri’s narrative voice is an idiosyncratic hotchpotch of Ghanaian English, Jamaican Patois, Cockney and Yoofspeak. I’m not familiar with Ghanaian English but I am sufficiently fluent in the others to be able to confirm that his speech patterns seem authentic to me. But don’t worry, kids, it’s still far easier to understand than Chaucer’s impenetrable Middle English, and no more difficult than Shakespeare’s Early Modern English. As far as his vocabulary is concerned, this clearly includes a number of words that he has misheard, misunderstood, misspelled, or spelled phonetically (you did notice that the book is called Pigeon English rather than Pidgin English, and recognise the significance of that… right?) and in some cases he’s just been told the wrong words by schoolmates, either because they’re as confused as he is or sometimes because they’re deliberately trying to be mischievous. Just like 11 year olds do.

So essentially it’s established from the outset that Harri is the absolute epitome of a literary tradition that English students, Cultural Marxists, and other so-called ‘intellectuals’ who actually read books refer to as an unreliable narrator. Consequently, if anyone has attempted to give you an impression of what this book’s about by quoting extracts from it out of context and without explaining that it is written in the voice of an 11-year-old child from another country and another culture with an idiosyncratic vocabulary, then I think you need to realise that you have been dealing with another unreliable narrator; otherwise, they are likely to make you look very foolish too.

As I’ve said, Harri is 11 years old, recently arrived from a village in Ghana, and trying to find his feet and make friends in a strange country. His new universe exists entirely in an area between the tunnel behind the shopping centre (I don’t even go in that tunnel. It’s just too hutious [scary].), the road going past his school, the road at the end of the river (McDonald’s is on the other side. I’ve never been there except with Mamma on the bus.) and the train tracks. The older boys are cool but some of the things they do are bad and hutious. Girls are stupid. But also intriguing. Some of Harri’s 13 year old sister Lydia’s friends have been known to suck off boys.

Yeah! This is what we’ve been told about, this is why this book’s been described as ‘Soft Porn’! This is why it needs to be banned and burned…

Some of the characters on Hollyoaks also suck each other off.

Wait… what? On Hollyoaks??? (It means a hard kiss). Do you see what I mean now about an unreliable narrator?

There is another passage where Harri uses the word ‘rape’…

OK, we’re getting the hang of this unreliable narrator thing now – fool me once and all that… so what does this naïve and unworldy 11 year old think the word ‘rape’ means?

Funny you should ask, because it doesn’t say exactly, but it’s a punishment a teacher administers as an adjunct to a detention and it’s ‘the same as dirty blows but even worse’. Dirty blows? Oh, that means a punch. It’s certainly nothing to do with what Harri refers to as “sexing someone”. So if anyone tries to suggest that teachers having non-consensual sexual intercourse with pupils is something that ever happens or is even alluded to in this book – let alone that the book somehow seeks to ‘normalise’ such behaviour, then we all know what sort of narrator they are now, don’t we, kids?

Harri does have a girlfriend; her name is Poppy.

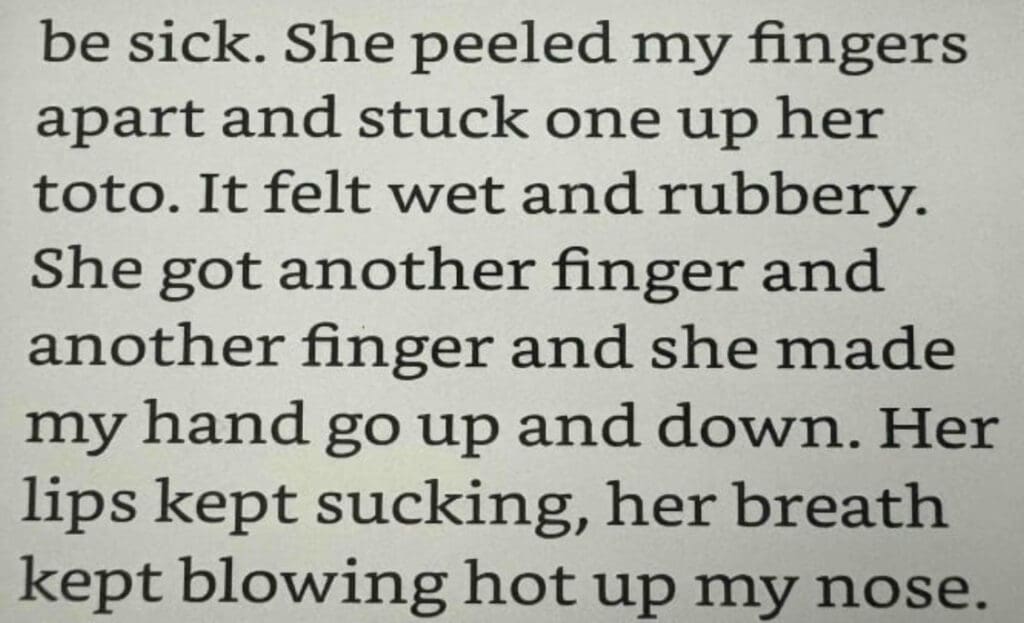

She gave him a piece of paper asking him if he wanted to be her boyfriend and he ticked the box that said yes and gave it back to her, so it’s official. They even hold hands. One of Lydia’s friends is determined that Harri needs to learn how to kiss his girlfriend, but Harri is reluctant to get involved with anything like that, and this is what gives rise to the section that people have been gleefully Googling and posting screenshots of as an alternative to actually reading the book.

Actually that probably is the most important scene in the book, at least from an eductional perspective, but definitely not for the reasons that some people have been suggesting – but the entire scene lasts for 2 pages (out of 267), so it is hardly representative of the book as a whole, and if anyone considers a description of an 11 year old boy being traumatised by a disturbed 13 year old girl to be in any way titillating or redolent of ‘Soft Porn’ then I have very serious concerns about the sort of material they actually are reading.

This is a description of a 13 year old girl exhibiting highly sexualised behaviour because she’s being physically and sexually abused by an older boyfriend who also happens to be a murderer.

The abuse is alluded to but not described in the book, because our 11 year old narrator is not equipped to even recognise it, let alone describe it.

And that brings us to what’s probably the most important issue here: we can either treat this fictional (but definitely not fictitious), damaged and vulnerable 13 year old girl, who is in very real danger, as an opportunity for us to learn ourselves and to teach our kids how to recognise when a real child is in real danger – and discuss how to respond appropriately – or we can use her as an opportunity to hone our skills in turning a blind eye and victim-blaming. The choice is ours. Or at least, it’s ours for as long as this book remains part of structured discussions supervised by experienced educators.

Sometimes we have to choose whether it’s better to protect our children from real sexual predators and grooming gangs or a few ‘hurty words’ in a book. Although, in fact, there’s actually very little swearing in the book – ironically Harri is extremely diligent about self-censoring – but I haven’t bothered to use a computer to count the expletives, because that’s essentially the 21st-century equivalent of going through a dictionary looking up all the rude words and underlining them, and at 14½ I outgrew that sort of immature behaviour several years ago.

What I can tell you is that the most terrible, the most awful, the most dreadful, and the most heinous thing Harri actually does in this book is to deliberately leave his footprints and sign his name in the wet concrete for a new disabled ramp outside the tower block where he lives.

My final verdict?

Asweh, it was dope-fine, bo-styles, brutal. Everybody agrees. 9/10

But I’d prefer to leave you with a final thought from the pigeon:

‘We prefer it when you walk around instead of through us. We like to be left in peace while we’re eating and performing our courtship rituals. We ask only for the same rights as you: we just want to live our lives, make a place for ourselves, room to shit and room to sleep, and room to raise our children. Don’t poison us just because we make a mess. You make a mess, too. There’s enough of everything to go round if we all stick to our fair share. Leave us be and there’ll be no trouble. Be kind to us and we’ll return the favour when the time for favours comes. Until then, peace be with you.’

Eddie Snide has been 14 ½ ever since 1977. His mum is still convinced that it’s just a silly phase that he’s going through and that he’ll grow out of it eventually. He would particularly like to express his thanks to Ron Swanson for being such an effective advocate for this book.