A teenager’s sudden descent into violence, driven by a toxic online subculture and emboldened by misogynistic influencers, has left his parents devastated. For many, it might sound like the plot of a gritty TV drama. For Jess and Rob, it is the nightmare they wake up to every day.

Their 14-year-old son, Harry, is now in care after a rapid and frightening spiral into aggression and control-driven behaviour. His parents — whose names have been changed to protect their identities — are still trying to comprehend how their kind, thoughtful son became consumed by an ideology that glorifies dominance over women and rejects empathy.

“Until he was 12, Harry was a wonderful boy,” Jess remembers. “Caring, bright, and funny.”

But everything began to change after an incident in school, when Harry was hit by a girl. His parents believe this moment planted a dangerous seed, one that would grow as Harry turned to the internet for answers.

“He became obsessed with being strong,” Jess explains. “And I think that experience created a resentment towards certain girls and women.”

Rob agrees, pointing to a growing fixation with male supremacy. “He had to be in charge, in every situation.”

Online Radicalisation at Home

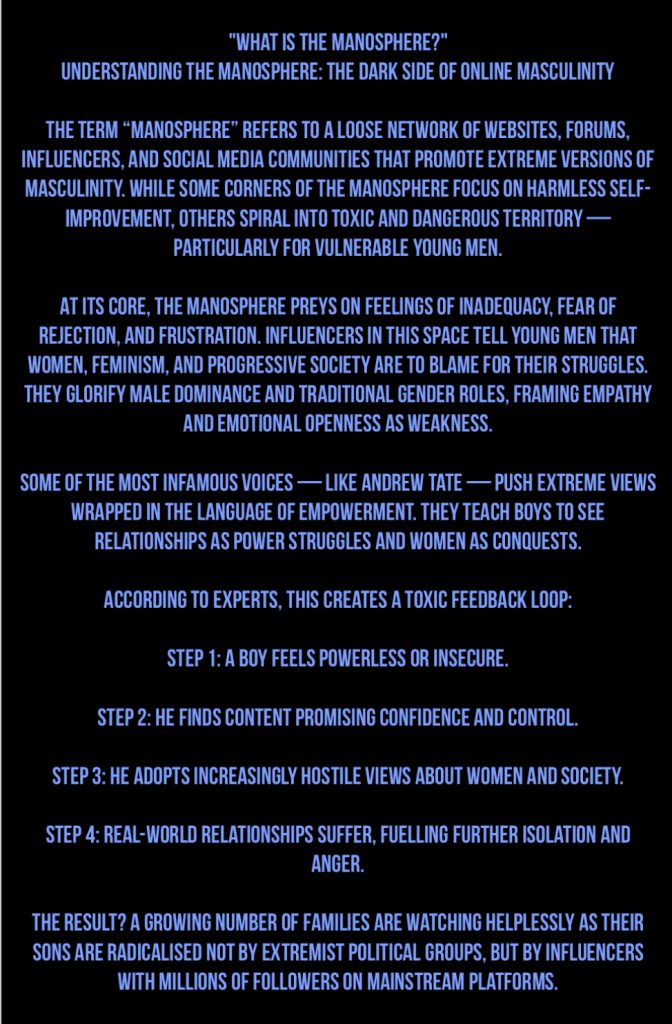

Harry’s story is not unique. Across the UK, families are facing an unsettling new threat — the radicalisation of their children, not by shadowy terrorist groups abroad, but by high-profile online influencers at home. Among the most infamous is Andrew Tate, a self-proclaimed misogynist whose videos and rhetoric have amassed millions of young followers globally.

Tate and others like him promote a brand of hyper-masculinity that frames women as inferior and men as rightful rulers of the world. They push narratives that claim men are victims of feminism, denied their rightful power. These messages, often disguised as fitness advice, financial freedom coaching, or “self-improvement”, find fertile ground among teenagers searching for identity, strength, and belonging.

Experts warn that boys like Harry, already vulnerable from trauma or mental health struggles, are particularly at risk.

“This is about more than just social media algorithms,” explains Dr Julia Peters, a psychologist specialising in adolescent behaviour. “It’s about a sense of powerlessness in their real lives. When influencers tell them they deserve power and control — especially over women — it can be intoxicating.”

In Harry’s case, the obsession with dominance soon turned to violence. The turning point came when he punched his mother, Jess. His parents called the police, desperately hoping the shock of legal consequences might halt the escalation.

It did not.

Instead, the violence intensified. Jess ended up hospitalised. Harry began lashing out at neighbours, friends — even threatening to stab a teacher at school.

“We probably called the police over 100 times,” Rob says, his voice heavy with despair. “Every time, we hoped it would be the moment that changed things. But it never was.”

A System at Breaking Point

Jess and Rob tried everything. They sought help from social services, mental health teams, and even begged for more intensive therapy. But their pleas went unanswered.

“We were told we were using too many resources,” Rob says, bitterly. “It felt like no-one wanted to take responsibility.”

They are not alone. Last year, PEGS (Parental Education Growth Support), an organisation supporting parents experiencing violence from their children, saw a 70% increase in calls for help. Founder Michelle John says services are overwhelmed.

“What we’re hearing, time and again, is that families are falling through the cracks,” she explains. “Referrals aren’t picked up because parents aren’t seen as victims of their children’s behaviour, and thresholds for intervention are absurdly high.”

Dr. Peters adds: “There’s this assumption that if the violence is coming from a child, it can’t be that serious. But the psychological trauma for parents is profound — they are living in constant fear in their own homes.”

The Dangerous Pull of the Online ‘Manosphere’

Part of the problem is the speed and reach of the toxic online ecosystem, often dubbed the “manosphere”. YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram — platforms teenagers use daily — are awash with clips of influencers boasting about their wealth, power, and ability to control women.

The messaging is cleverly disguised. It starts with seemingly harmless content: workout routines, advice on making money, and motivational speeches about self-improvement. But quickly, it escalates into an ideology of entitlement, resentment, and hatred.

Bright Star Boxing Academy in Shropshire has been helping to steer young men away from these dangerous paths. Its founder, Joe Lockley, says, “The biggest cause of this violent behaviour is mental health. These kids feel like they don’t belong, and they’re desperate for power in their lives.”

Social media fills that void. “It’s so easy to fall in,” Lockley adds. “You feel powerless in your real life, but online you’re told you can be a king. That’s incredibly seductive.”

Ethan, now 18, knows this all too well. Arrested several times by the age of 14, he describes how social media fed his anxiety, anger, and eventually self-loathing.

“I’d see people with perfect bodies, flashy cars, and millions in the bank,” he recalls. “I felt like I could never get there. It made me so angry, and that anger turned into hatred.”

With support from Bright Star, Ethan has managed to rebuild his life. “Without them, I’d either be in prison or dead,” he says bluntly.

A Cry for Urgent Action

For Jess and Rob, these stories of recovery offer some small comfort — but they know it came too late for their family.

“We feel like we’ve lost him to the internet,” Jess says quietly.

The government insists change is coming. “We are investing over £50 million in specialist support for schools, mental health hubs, and professional support,” a spokesperson said.

But for parents living this nightmare right now, these promises feel painfully distant. Until there is a serious reckoning with the toxic underbelly of online culture and genuine investment in early intervention, families like Jess and Rob’s will continue to suffer.

As Jess puts it, “We did everything we could. But it wasn’t enough. And that is the hardest thing to live with.”