From 2015 to 2020 Jeremy Corbyn, as leader of the Labour Party, rejected Peter Mandelson and what he stood for. Mandelson thus sought to ensure Corbyn was never prime minister. And he did not act alone.

The following, though, focuses on what many may not be aware of. Mandelson was identified nearly forty years ago, and few did anything to prevent it.

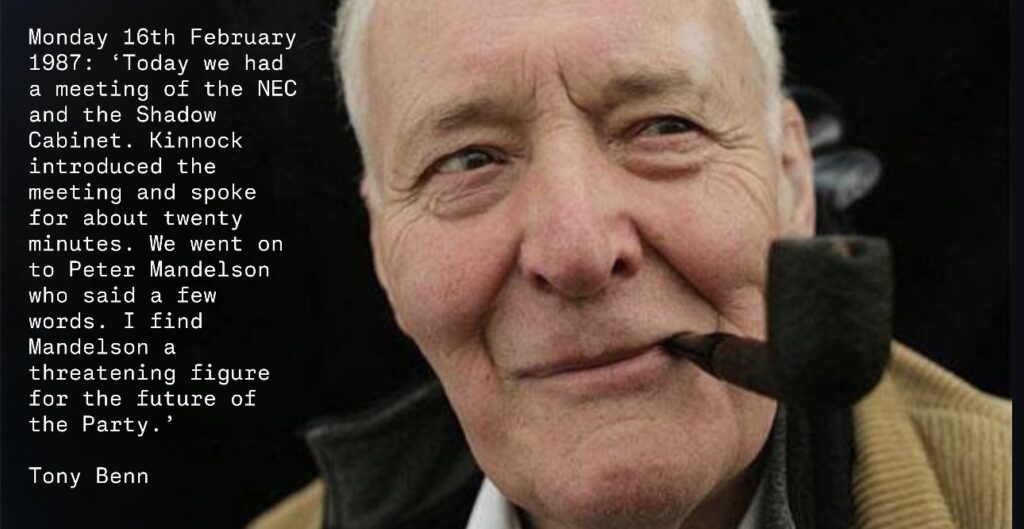

Tony Benn’s warning about Peter Mandelson was not moral panic. It was structural. When Benn wrote in 1987 that Mandelson was “a threatening figure for the future of the Party,” he was not anticipating a scandal sheet headline or a tabloid exposé. He was diagnosing a politics that would ultimately detach power from accountability so completely that nothing would shock it anymore.

The Epstein revelations did not create the Mandelson problem. They merely exposed it.

The Pattern Before the Scandal

Long before Jeffrey Epstein’s name entered public consciousness, Mandelson had already built a career defined by proximity to power without visible restraint. His critics never accused him of being stupid or careless. Quite the opposite. They accused him of believing that rules were for other people, that the truly important operated above them.

This is why his repeated returns after resignation mattered so much. Each scandal that failed to end his career reinforced the same lesson: accountability was negotiable, consequences optional, and reputation endlessly recyclable for those deemed “too useful to lose.”

That lesson has infected British politics ever since.

Epstein Was Not an Aberration — It Was Exposure

When Mandelson’s name appeared in connection with Epstein, the reaction among his critics was not disbelief. It was grim recognition.

The revelations—that Mandelson had social contact with Epstein, that he stayed at Epstein’s New York property, and that he continued the association after Epstein’s conviction—did not prove criminal wrongdoing. That is not the point, and serious critics do not pretend otherwise.

The point is judgement. The point is culture.

Epstein was not a hidden figure in elite circles after his conviction. He was an open secret. Anyone moving comfortably in global elite networks knew what he represented: money, access, kompromat, and the corrosion of moral boundaries in exchange for influence.

For a figure like Mandelson, hyper-attuned to reputation, optics and risk, ignorance is not a credible defence. The question is not “did he know?” The question is, why did it not matter?

Power Without Moral Cost

Mandelson’s defenders retreat to technicalities: no charges, no proof, no illegality. This is revealing. It treats politics as a legal compliance exercise rather than a moral one.

Benn would have recognised this instantly.

The Epstein association crystallised what critics had argued for decades: Mandelson operates in a world where power is the primary currency, and moral cost is secondary, if it is considered at all. The same instincts that normalised opaque loans, blurred boundaries, revolving doors and elite impunity also normalised social proximity to someone like Epstein.

This is not coincidence. It is continuity.

The Elite Bubble Made Flesh

Epstein represented the ugliest extreme of elite insulation: a man protected by wealth, connections and silence until exposure became unavoidable. Mandelson’s comfort within overlapping worlds of politics, finance, diplomacy and consultancy reflects the same ecosystem; one in which access substitutes for accountability.

That is why the Epstein revelations resonated so deeply. They felt less like a shocking deviation and more like the logical endpoint of a career spent moving seamlessly through unaccountable spaces.

To critics, the scandal did not tarnish Mandelson’s reputation. It confirmed it.

The Party That Learned Nothing

What is truly damning is not Mandelson’s behaviour, but Labour’s inability, or refusal, to reckon with what he represents.

Even now, Mandelson is treated as an elder statesman. A sage. A voice to be consulted. His presence in contemporary Labour discourse is a reminder that nothing fundamental has changed. The party still values proximity to power over moral clarity. It still confuses seriousness with cynicism. It still believes the electorate cares more about polish than principle.

The Epstein episode should have forced a cultural reckoning. Instead, it was managed, minimised, and quietly moved past.

That, more than anything, is the Mandelson legacy.

From Benn to Now: The Through-Line

Benn feared Mandelson because he understood that once politics loses its moral centre, it compensates with control. That compensation has defined the present day.

A party terrified of internal democracy.

A leadership culture obsessed with discipline but allergic to responsibility.

A political class more scandal-proof than scandal-averse.

When today’s Labour leadership insists on “professionalism” while refusing to confront the ethical rot of elite politics, it is reenacting Mandelsonism in real time. When it closes ranks rather than opening debate, it confirms Benn’s fear that Labour would become a vehicle for power rather than a challenge to it.

Epstein as Symbol, Not Exception

Jeffrey Epstein was not simply a criminal. He was a stress test of systems, institutions, and people. Many failed it. Mandelson’s failure was probably criminal, but it was certainly political and moral. He did what he has always done: stayed close to power, trusted his own judgement, and assumed consequences were for others.

That is why this matters now.

In an era of collapsing trust, rampant cynicism and democratic fatigue, politics cannot afford figures who embody impunity. Yet Labour still cannot quite let go of the worldview Mandelson represents. It still treats criticism as disloyalty and accountability as inconvenience.

The Threat, Completed

Tony Benn called Mandelson “threatening” because he foresaw a politics emptied of ethical seriousness. The Epstein revelations did not introduce something new; they simply illuminated the destination.

A politics where elite networks matter more than public trust.

Where judgement is secondary to access.

Where survival replaces responsibility.

That is the threat fulfilled.

Until Labour confronts this legacy—not cosmetically, not rhetorically, but structurally — it will remain haunted by the figure Benn warned about. Not because Peter Mandelson still holds office, but because his politics still do.

And that, far more than any single scandal, is the real indictment.

And if you do not believe me, then believe Barry Gardiner MP:

Barry Gardiner with the most truthful 105 seconds you’ll be likely to see this week. pic.twitter.com/ToryezXOe2

— Matthew (@MatthewTorbitt) February 5, 2026