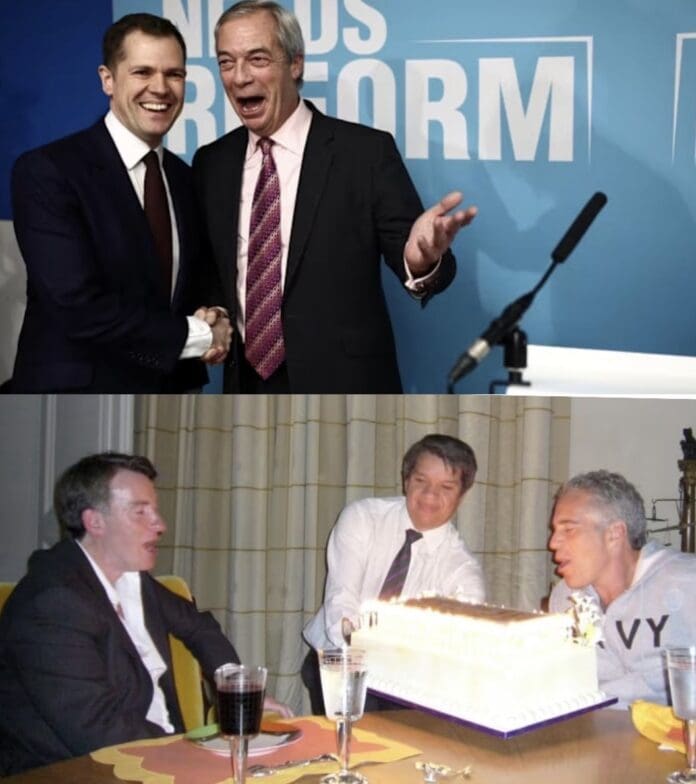

There comes a point in every political project when its self-image finally collapses under the weight of reality. Reform UK may be approaching that moment. Having once styled itself as a bracing anti-establishment revolt, it now increasingly resembles a refuge for careerists, opportunists and figures whose judgment has failed them elsewhere. In that context, there is one man whose arrival would feel not merely plausible but inevitable: the quite dreadful Peter Mandelson.

At first blush, Mandelson appears an awkward fit. Reform UK claims to despise the political class; Mandelson is its purest distillation. He is the architect of spin over substance, the man who helped normalise the idea that politics is a game of presentation rather than principle. Yet this apparent mismatch dissolves on closer inspection. Reform UK’s rhetoric may rail against elites, but its behaviour shows a growing comfort with them; provided they are useful, loud, or capable of drawing attention. Mandelson, for all his reputational baggage, excels at exactly that.

The Art of Surviving Anything

Mandelson’s defining political talent has never been conviction. It is survival. Across decades in public life, he has demonstrated a near-unique ability to outlast scandal, reshape narratives, and re-enter positions of influence long after most observers assumed his career was finished. In today’s Britain, where disgrace is increasingly temporary and rehabilitation is often a matter of timing, that skill is perversely valuable.

Reform UK has shown a similar instinct. Figures who fall out with other parties, who carry controversy with them, or who struggle to meet basic standards elsewhere often find a welcoming platform. The party presents this as “free speech” or “telling it like it is”. Critics see something else: an organisation that treats controversy not as a warning sign but as a form of fuel.

Mandelson would not need to adjust his political instincts to thrive in such an environment. He has spent his entire career navigating contradiction, moral ambiguity and reputational damage with a smile that suggests none of it truly matters.

Epstein and the Question of Judgment

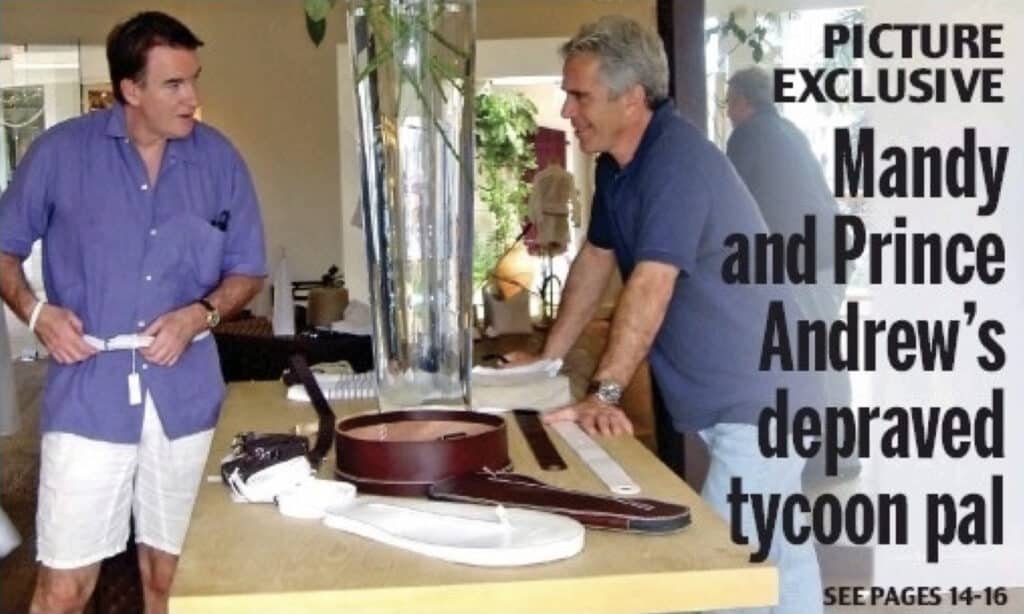

What elevates Mandelson from merely cynical to genuinely toxic, however, is his association with Jeffrey Epstein. Epstein, a convicted sex offender and later accused of extensive sexual exploitation and trafficking of minors, became one of the most notorious figures of the modern era precisely because of the powerful people who continued to associate with him after his crimes were known.

Mandelson’s connection to Epstein was not fleeting or incidental. He maintained contact after Epstein’s 2008 conviction, socialised with him, and even offered advice during Epstein’s attempts to rehabilitate his image and secure early release. Written correspondence later revealed Mandelson referring to Epstein in warmly personal terms — language that jarred profoundly with the scale and nature of Epstein’s offences.

Ultimately, this association cost Mandelson his diplomatic role and forced public apologies. Mandelson has said he regrets the relationship and was unaware of the full extent of Epstein’s crimes. That may or may not be true. What is beyond dispute is that the episode revealed a catastrophic failure of judgment and a comfort with power that overrode basic moral caution.

For a party that claims to stand for decency against a corrupt elite, this should be disqualifying. For Reform UK as it currently exists, it looks increasingly like a qualification.

Reform UK’s Own Pattern of Scandal

Reform UK cannot pretend that it approaches issues of conduct, safeguarding or workplace culture from a position of moral clarity. The party’s recent history is littered with controversies involving bullying, harassment, offensive behaviour and failures of vetting, some of them directly affecting women working within or around the party.

Senior figures and MPs have been suspended or investigated following complaints of harassment and intimidation. Independent findings have pointed to credible evidence of unlawful behaviour in some cases. Elsewhere, candidates have been dropped after social media posts trivialising or celebrating known sexual abusers came to light, raising serious questions about how such individuals passed even minimal scrutiny.

Alongside this is the party’s often inflammatory rhetoric around sexual crime, particularly grooming gangs. Critics, including survivor groups, have accused Reform UK of exploiting the issue for political gain, using the language of victimhood selectively while showing little interest in safeguarding, nuance or accountability within its own ranks.

The pattern is not one of isolated mistakes but of a political culture that repeatedly reacts too late, minimises harm, and treats scandal as an inconvenience rather than a signal for reform.

A Shared Contempt for the Public

This is where Mandelson truly aligns with Reform UK. Both operate on an unspoken assumption that the public is less interested in integrity than in performance. Where Mandelson spoke of “message discipline” and “expectation management”, Reform UK prefers the language of “common sense” and “plain speaking”. The difference is stylistic, not moral.

In both cases, voters are treated as an audience to be handled, not citizens to be respected. Apologies are tactical. Accountability is conditional. Survival is paramount.

Mandelson’s association with Epstein did not end his career because the modern political ecosystem rarely demands genuine consequence. Reform UK’s repeated scandals have not slowed its media presence because outrage, in the short term, often benefits those who thrive on attention. They are products of the same political logic; one polished, the other populist, but equally hollow.

The Perfect Symbol

If Peter Mandelson were to join Reform UK, it would not be an aberration. It would be a moment of clarity. It would strip away the last remaining pretence that the party represents a clean break from the political culture it claims to despise.

Instead, it would stand exposed as something else entirely: a coalition of grievance, opportunism and recycled political ambition, united not by principle but by resentment and self-interest.

Mandelson would bring with him experience, connections and an unparalleled ability to weather disgrace. Reform UK would offer him a platform that no longer cares about optics, only noise. In that sense, the match would be perfect — not despite the scandals, but because of them.

If Reform UK wants to show the country what it has truly become, it would struggle to find a more fitting recruit than Peter Mandelson.