I’ve used these figures before, in a post I wrote some months ago in response to claims by Tory MP and apologist for the rich, Jacob Rees-Mogg. However, the claims have surfaced again as defenders of the poor, oppressed wealthy have rushed to rubbish Labour’s idea of a ‘jobs guarantee’ for the long-term unemployed. So it seemed appropriate to write a new article highlighting the figures – and the fallacy they’re used to support.

Think what you will about Labour’s idea (and my own thoughts are tending toward the ‘worthy effort but try again’ variety), it’s at least an attempt to do something for people who are on the employment scrapheap through no fault of their own.

But it has drawn the predictable response from the Tories, with the ludicrous Grant Shapps/Michael Green saying that it would mean Labour ‘spending the same money twice‘, even though Labour have been very clear that if the idea went ahead it would be funded by an additional £1 billion of revenue generated by reducing tax relief currently enjoyed by the richest on money that they put into their pension pots.

A slightly more logically coherent, but still wholly incorrect, response came from George Bull, Senior Tax Partner at tax and accountancy firm Baker Tilly, on the BBC News channel. It’s one which I have seen echoed around the web since, which is why I’m re-blogging these figures – whose logic is, I believe, incontestible.

Mr Bull said:

Why has [Ed Balls] produced..all the noise..by explaining that there will be an extra tax charge to pay for it? He could simply pay for this out of normal taxation.

In other words, ‘Why tax the rich to pay for this when you could tax the less well-off for it?’ Mr Bull went on to accuse the Shadow Chancellor of being ‘socially divisive‘ and ‘corrosive‘ by targeting the rich as the source of funds for the proposed new scheme. He then trotted out the old favourite:

The top 1% of earners pay 27% of tax revenues. They already pay their share.

It’s a very convincing argument, on the face of it. It just happens to be wholly false. Let’s see why.

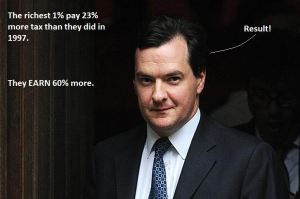

In Rees-Mogg’s contribution to Newsnight back in September 2012, he put forward much the same argument. He stated that the richest 1% earn 13% of the country’s total income, but pay 26% of total tax revenue. He added that, because the rich paid 21% of tax revenues in 1997 and 26% now (not 27% as Mr Bull claimed, but we won’t quibble over 1% now), they were definitely paying their fair share. Or, as David Cameron might put it, ‘we are all in it together’.

The big problem with his logic is exposed by looking – as he did – at the situation in 1997 compared to now. Except not just at the contributions to tax revenue, but also at earnings.

A BBC website article at the beginning of 2012 analysed the increase in UK income inequality from 1997 to 2007. It showed that the average income of the top 1% of UK earners increased from £187,989 to £301,325 – an increase of just over 60% (income of the top 0.1% almost doubled). And these are just the ‘declared income’ figures – many of the wealthy find all kinds of ways to categorise their income so that it’s not declared as income at all, because once you earn that much the cost of paying someone to find loopholes becomes insignificant.

Since the top 1% have continued to increase their wealth since 2007, we can safely assume that the difference is even greater now. During the same 1997-2007 period, average incomes for the bottom 90% increased by only 17.6% – and for the lowest earners by far less.

The increase in the tax contribution by the top 1%, from 21% in 1997 to 26% now, means that their contribution is around 23% higher (or 28.5% if you go with the 27% current figure), relative to what they were paying in 1997. Either figure is far less than the increase of at least 60% (and probably considerably more) in their incomes.

This means that the wealthiest are now paying substantially less toward our national upkeep than they were 15 years ago, relative to their wealth.

Rees-Mogg made another point which bears on the issue of the last few days, too – though not in the way he intended. He talked about historical tax revenues, pointing out (more or less correctly) that tax revenues have rarely exceeded 38% of GDP. Of course, the fact that it has been the case in the past doesn’t prove it can’t be different in the future – just as those investment ads say: ‘Past returns do not guarantee future performance‘.

But he was a lot more off-target than that. Here’s what he gave away without meaning to:

Projected tax revenue for the current financial year is only 35.5% of expected GDP. Since that’s an expected figure rather than a definite one, let’s look at the 2011/12 year instead: in the last fiscal year, government revenues from income tax were £550.6 billion, or 35.7% of GDP of £1.542 trillion.

The difference between 38% and 35.7% might not seem like so much. But if the government had taxed in order to achieve the ‘magic’ 38% figure, it would have generated an additional tax take of £35.47 billion.

Or, to put that into terms that make concrete sense: enough to make the welfare cuts so far of £10bn AND the targeted NHS cuts of £20bn completely unnecessary – AND to cover the appr. £4bn shortfall in public sector pensions.

In spite of the protestations of those trying to protect their own huge wealth and that of their clients/donors, one thing is clear:

Whatever you think of Labour’s ‘job guarantee’ scheme, the richest are not paying their share – and there is plenty of room for additional taxes on them in order to fund good ideas to help those most in need. We are not ‘all in it together’. Not by a long, long way.

Fairness? Pull the other one.