All eyes will be fixed on the waters of Weymouth Bay and Portland harbour this summer for the Olympic Sailing events, but what treasures and mysteries lies beneath it?

There are reportedly hundreds of shipwrecks in the waters surrounding Weymouth and Portland which date back to the 16thCentury. As they lie on the sea bed; motionless in time, each wreck has its own unique story and place in history which is both fascinating and tragic.

The ‘Himalaya’ was built in 1853 for the P&O Cruise Line. At the time it was the largest passenger carrier in the world, weighing 3,553 tonnes and was twice the size of any other ship in their fleet. Just one year after she was built, the Crimean war broke out and the admiralty bought her for £130,000 to be used as a troop ship, transporting soldiers to India.

HMS Himalaya served her purpose well, making trooping voyages to India until 1894 after which she was converted into a coal hulk and anchored in Portland Harbour. On the 12thJune 1940 she was attacked by German Bombers in an air raid during the 2ndWorld War. She sank almost immediately, and scattered pieces of her wreck lie in Portland Harbour to this day. No lives were lost as this vessel sank to its final resting place on the seabed.

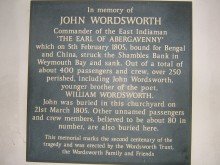

Sadly, ‘The Earl of Abergavenny’ was not so lucky. The sinking of this ship caused one of the largest loss of lives of all the ill fated shipwrecks on the sea bed of Weymouth and Portland Bay. The death of over 250 men, including its Captain John Wordsworth, brother to the famous English Poet Laureate William Wordsworth, makes her sinking even more tragic.

The Earl Of Abergavenny was part of the East India Company fleet; a joint stock company specialising in trading with the East Indies. In 1805, The Earl of Abergavenny was steaming towards China on a lucrative trip to buy and sell precious goods with a convoy of other ships, including HMS Weymouth. The trip had already been fraught with problems, as bad weather had caused her to collide with ‘The Warrren Hastings’ but she had escaped with minimal damage and so was able to continue her journey.

The Earl of Abergavenny reached the ‘Portland Roads’ (Portland Harbour) to wait for fairer weather before continuing the trip. As was customary, a pilot boarded the vessel to navigate it around the ‘Shambles’ – a dangerous area of shingle and coarse sand just 2 miles out to sea. However, the pilot in charge made a fatal error and soon the ship was grounded at the Shambles, taking on more water by the minute. The sea was rough and even after the ship freed itself from the Shambles after 2 and a half hours, it had taken on too much water for it to be steered towards safety.

The Cutters (small boats to enable transportation between land and the ship) were not launched as it is thought that the Captain and his crew concentrated on keeping the ship afloat for as long as possible, with the hope of steering her to the safety of Weymouth Bay, just a few miles away.

At the realisation that the ship would certainly sink, Captain John Wordsworth replied: “It cannot be helped. God’s will be done.”

At 11pm on 5thFebruary 1805 over 260 men died at sea as The Earl of Abergavenny finally sank in shallow waters. Some threw themselves into the icy water, trying to use debris from the ship to get to shore, others held onto the rigging until the last moment, trying to stay above the water level. Those who did not drown died shortly after from exposure and hypothermia. Despite firing guns to call for help, other ships could not get close enough to assist them due to the rough sea conditions.

The death of Captain John Wordsworth affected his brother William Wordsworth very deeply. References to his grief can be found in his poetry:

“Not for a moment could I now behold

A smiling sea, and be what I have been:

The feeling of my loss will ne’er be old…”

“Elegiac Stanzas” – William Wordsworth 1806

The bodies of 80 men, including Captain John Wordsworth were recovered and buried at All Saints Church in Wyke Regis on the 21stMarch 1805. Today, the headstones no longer remain, but a plaque lies inside the church in remembrance of John Wordsworth and his crew. There is also a memorial at the ‘Stone Pier’ in Weymouth which was placed there on the 200 year anniversary of the sinking.

The watery graveyard of Weymouth and Portland Harbour is famous and unique in that ships and aircraft have sunk in varying circumstances: a result of nature, war, human error and even as part of Military tactics to prevent torpedo attack on the ‘Portland Roads’. There is also a huge variety of vessels including Military Submarines (the ‘M2’ sunk 1932), Battleships (HMS Hood – deliberately sunk 1914) Steamships (The Countess of Erne – sunk 1935) and even aircraft (The Sea Vixen – crashed and sunk 1966) for divers to explore, allowing these vessels to be rediscovered again and again.

Whilst providing a stage for the Olympic Sailing events, beneath Weymouth and Portland Harbour lays a jigsaw of our maritime heritage which has been preserved over a huge period of time. So, next time we take a Sunday afternoon stroll along the beach, it might be nice to applaud the ships beneath the sea, as well as the ones sailing on top of it.

By Sally Welbourn

References:

Rachel Knowles ‘Regency History’ Blog, specifically her article about the sinking of the Earl of Abergavenny – https://www.regencyhistory.net/2012/02/wreck-of-abergavenny.html

National Maritime Museum – www.rmg.co.uk

Queens Royal Surreys Regiment Website – www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk