The scandal that started in the UK is now sweeping Europe – it’s that ready-made meals in British supermarkets labelled as beef have turned out to contain anything up to 100% horse meat. So consumers are paying for more expensive beef and being fed horse, with the added health risk that this horse meat could contain dangerous veterinary drugs harmful to humans. The extent of the fraud is yet to be determined, but it shows once again that when profit rules, health and honesty disappear.

The Great Recession has increased contaminated meat risks, as cost-cutting has driven British consumers to low-cost ready meals while checks made on meat provenance have been cut back. As Dr Louise Manning, senior lecturer in food production management at the Royal Agricultural College, put it ” Since the recession in 2008 there has been a drive for affordable food”, resulting in bigger supply chains. “The challenge is that as the supply chain becomes bigger and bigger then consumers have to rely on trust,” she said. Yet budgets for trading standards and environmental health, meanwhile, have been cut by 32% in real terms per person since 2009, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the independent economic research body. And since the BSE crisis in the 1990s, the meat inspection workforce under the Food Standards Agency has more than halved to 800. “Food fraud is a fact,” Manning says, arguing that the bigger the supply chain, the greater the uncertainty for consumers. “We have a truly global supply chain,” she said. “With chicken products most of the meat comes from Thailand. If you buy ready meals the meat could come from Asia or Brazil.”

Since 2003, Britain has eaten more ‘ready meals’ than the rest of Europe put together, and over half of all the savoury snacks and crisps eaten on the continent as a whole. The average amount spent on food ingredients for a primary school meal in 2003 was 35 pence: a quarter of the sum allocated to feeding a guard dog in the British army. In 2005, a staggering 40% of all people admitted into hospital were found to be suffering from malnutrition, as officially defined.

Most disturbing of all are the statistics for obesity. Thanks in major part to the gradual abandonment of homemade meals and the adoption of serial snacks and convenience food, Britain is lumbering towards a fat epidemic. Around two-thirds of adult males, and more than half of adult females, are now either overweight (fat) or obese (extremely fat). Obesity has grown by 300% over the last 20 years. More than a fifth of Britain’s adult population is obese – and that’s just the grown ups. Nearly one third of British children aged 2-15 are either overweight or obese. Obesity is rising twice as fast among children as adults. Nowadays, nearly 16% of children aged 6-15 are now officially obese – three times as many as a decade ago – and this puts them at risk. In 2002, cases of maturity-onset diabetes in obese British children were reported for the first time. Fatty deposits – one of the first signs of heart disease – have also been identified in the arteries of teenagers. I don’t need to remind readers that the story is much the same, if not worse, in the US.

Since the beginning of modern industrial capitalism with the commoditisation of food, food fraud and adulteration has been endemic. In a gruesome passage in chapter 10 of the first volume of Capital, Karl Marx wrote of the ‘incredible adulteration of bread’ in Victorian London, and used a report of a Royal Commission of Inquiry to reveal that the London worker, ‘had to eat daily in his bread a certain quantity of human perspiration mixed with the discharge of abscesses, cobwebs, dead cockroaches, and putrid German yeast, without counting alum, sand, and other agreeable mineral ingredients’.

It was the same story in America. Charles Dickens, who visited in 1842, was stunned and appalled by what American capitalists would do for the sake of profit. Taking a page from the British, American manufacturers, distributors and vendors of food began tampering with their products en masse — bulking out supplies with cheap filler, using dangerous additives to mask spoilage or to give foodstuffs a more appealing color. A committee of would-be reformers who met in Boston in 1859 launched one of the first studies of American food purity and their findings make for less-than-appetizing reading: candy was found to contain arsenic and dyed with copper chloride; conniving brewers mixed extracts of “nux vomica,” a tree that yields strychnine, to simulate the bitter taste of hops. Pickles contained copper sulphate, and custard powders yielded traces of lead. Sugar was blended with plaster of Paris, as was flour. Milk had been watered down, then bulked up with chalk and sheep’s brains. Hundred-pound bags of coffee labeled “Fine Old Java” turned out to consist of three-fifths dried peas, one-fifth chicory, and only one-fifth coffee. Though there was the occasional clumsy attempt at domestic reform by midcentury — most famously in response to the practice of selling “swill milk” taken from diseased cows force-fed a diet of toxic refuse produced by liquor distilleries — little changed.

With the development of an international food trade, the scandals spread. One of the first international scandals involved “oleo-margarine,” a butter substitute originally made from an alchemical process involving beef fat, cattle stomach, and for good measure, finely diced cow, hog, and ewe udders. This “greasy counterfeit,” as one critic called it, was shipped to Europe as genuine butter, leading to a precipitous decline in butter exports by the mid-1880s. The same decade saw a similar, though less unsettling problem as British authorities discovered that lard imported from the United States was often adulterated with cottonseed oil. Even worse was the meatpacking industry, whose practices prompted a trade war with several European nations. In 1879, when Germany accused the United States of exporting pork contaminated with trichinae worms and cholera. That led several countries to boycott American pork. Similar scares over beef infected with a lung disease intensified these trade battles.

The 20th-century malfeasance of the industry is well known: “deviled ham” made of beef fat, tripe, and veal byproducts; sausages made from tubercular pork; and, as Upton Sinclair explained in his horrifying book, The Jungle, about the Chicago meat packing industry, lard containing traces of the occasional human victim of workplace accidents.

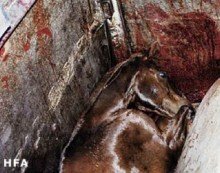

Flogging dead horses is the least of the scandals in the history of the global capitalist food industry.

Michael Roberts