(note this review contains spoilers)

There has been a lot of carping by reviewers about alleged historical inaccuracies in Ridley Scott’s latest film Napoleon with one writer, Simon Scarrow, claiming it was ‘the worst film’ he had seen in the last few years and that it had left him ‘gasping and often watching events unfold through my fingers’. In fact, some reviewers seemed to be trying to outdo each other in condemning the film, describing it as:

“Ken and Barbie under the Empire” (Le Figaro)

“deeply clumsy, unnatural and unintentionally funny,” (GQ France)

“very sure of its inanity.” (Libération)

“the historical revenge of Ridley Scott, the Englishman,” (Le Canard Enchaîné)

“Execrable” (The European Conservative)

A “toothless depiction that lacked depth & intrigue” (Gaurav Krishnan, Medium)

A “debacle” and an “industrial disaster of a film” (Agnès Poirier in The Guardian)

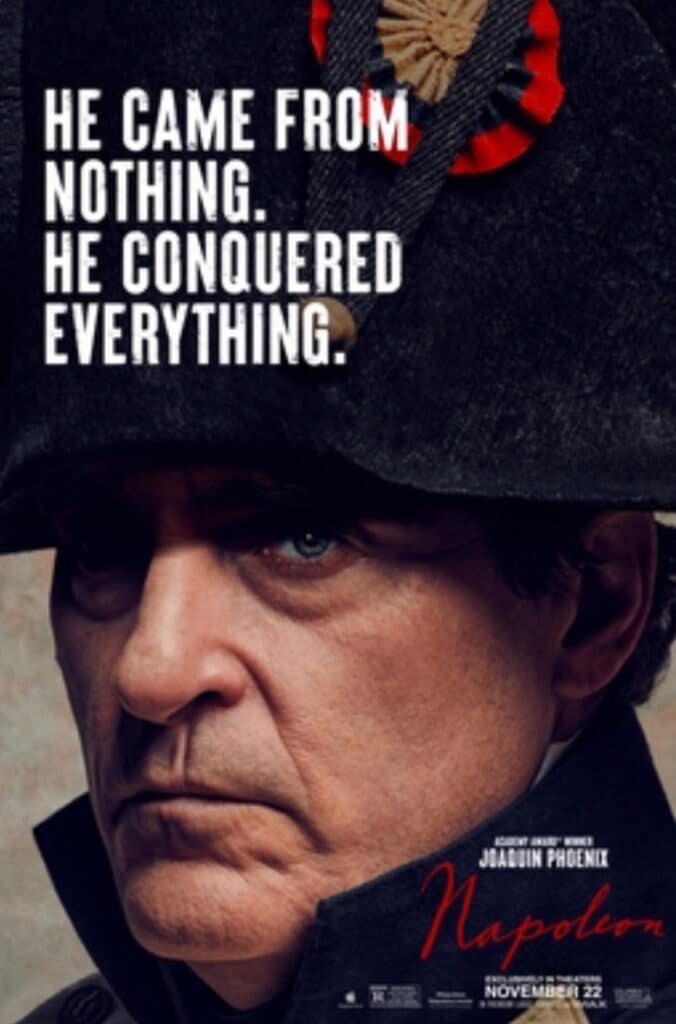

To judge for themselves, a group of students and staff from Bournemouth University’s History and Politics programmes attended a screening of the newly released epic, starring a brooding Joachim Phoenix as Napoleon and Vanessa Kirby (excellent) as Joséphine, at the fabulously old-school, red velvet, art deco Regent Cinema in Christchurch on Tuesday.

The first thing to say is that everyone attending enjoyed the film, which, at two hours and 38 minutes did not feel that long, and which delivered a recreation of historical events such as Napoleon crowning himself Emperor, his vast army’s retreat from Moscow or the Battle of Waterloo in a compelling and visually sumptuous manner. Scott’s early career as an advertising director can still be glimpsed in the ‘beautiful’ rendering in slow motion of horses and soldiers drowning beneath the frozen lake at the Battle of Austerlitz. Turning the deaths of thousands on the battlefield into an elegant spectacle can diminish the sense of threat and horror, but overall, the battle sequences – highly truncated in this release – are impressive and visceral. Did troops at Waterloo hide behind banks of earth (not trenches as Scarrow alleges in his review)? Well, you will have to research further to find out.

Scarrow’s diatribe against Scott’s Napoleon includes the following complaints:

“Along the way we ‘learn’ that Napoleon abandoned his army in Egypt because he was cross about Josephine’s infidelity. That the Battle of Waterloo was fought from trenches. That the fort guarding the approaches to Toulon was smack bang in the town itself. That the British artillery used split trail gun carriages. That Austerlitz was fought on ice. At every point, the representation of history takes a false step”.

What great screened history makes you do is go and read the history to discover more about the details. The frozen lake at Austerlitz was in fact frozen fishponds and the history books tell us that horses and equipment were indeed lost in the water, and two thousand, two hundred, or perhaps just two soldiers were drowned there, depending on which version of that history you read.

If you want to see an accurate recreation of the battle of Waterloo, perhaps watch a video of a battle reenactment (plenty available on Youtube) and check if the right gun carriages have been used. It won’t be as exciting as Scott’s film with his dramatic charges and loving attention to flags, uniforms, or characters such as Wellington (played by Rupert Everett) who sneers at Napoleon through his telescope.

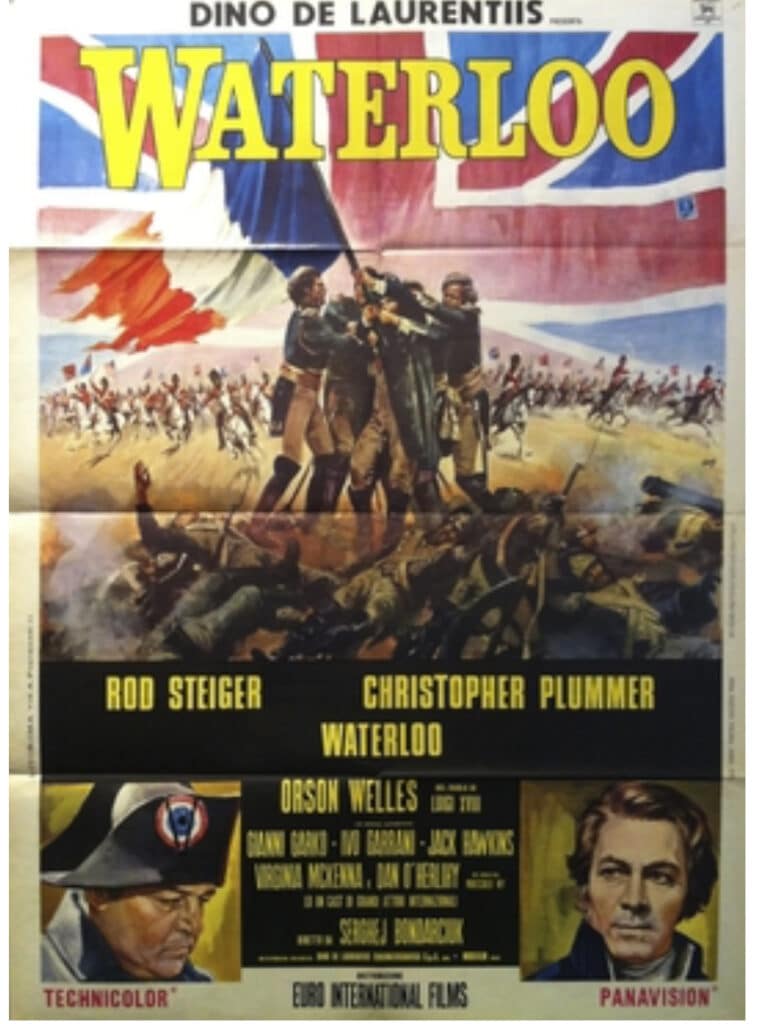

Alternatively, for a more ‘accurate account’ you might check out the excellent 1970 film Waterloo directed by Sergey Bondarchuk which shows Napoleon, played by Rod Steiger, as far too ill to ride into battle as he does in Scott’s version. Bondarchuk’s feature film used thousands of Russian troops as extras and is probably as close as you will ever get to a CGI free blow-by-blow account of Waterloo which also offers a more developed portrait of Wellington (played by Christopher Plummer), but the film only deals with that one battle. Scott’s film tries to compress all of Napoleon’s major battles and private life into less than three hours. It is a minor miracle it is as coherent as it is.

And while Scott may play with events in a way that historians cannot (he was not at the execution of Marie Antoinette, for instance) he does select and frame events, characters, and versions of history to suit his narrative – much as historians do. His relationship with Josephine is a core focus, so when he learns of her infidelity, Napoleon leaves his troops in Egypt. Perhaps in the one hour longer version to be streamed on Apple+, or the “fantastic” four and a half hour director’s cut I hope we get to see some day, will show that Scott was quite aware (as he must have been) that Napoleon was also driven from Egypt by the British who attacked his fleet in the Battle of the Nile – and from Palestine (where Napoleon planned to announce a state for Jews).

Of course, trying to pack any more details like this would require a thirty-hour mini-series – along the lines of The Crown. Incidentally, that is, more or less, what director Abel Gance intended with his epic five and a half hour silent epic Napoleon (1927) which only took the story up to Napoleon’s invasion of Italy in 1797 (the film stops there because it was intended to be part one of six, but Gance never raised the money to make the other five).

As we forced marched our way back in the cold night air to catch a train from Christchurch station after the film we reflected on the fact that two divisions of Napoleon’s troops marched for 70 miles in two days before the battle of Austerlitz, which put our eleven minute walk to the station in context. A quick check with what IMDB rating the students would have given it came up with an average of around 8. ‘It needs time to settle’ one said when pressed, which is true. The further we got from the cinema the more questions were asked about how little of Napoleon’s famous charisma we saw or how much was lost through compressing events and reducing characters to brief soundbites. I wanted to see much more of Paul Barras, for instance (played by the brilliant French-Algerian actor Tahar Rahim).

Ultimately this is the dilemma of trying to tell such a titanic story in less than three hours and why streaming services may well be the only way to tell long-form screened history in a way that might satisfy audiences and historians. However, as the raging controversies over the latest Crown episodes indicates, history is deeply political and the more invested we are in that history, the more contested it becomes. This is why as The Crown inched closer to the living memory of British reviewers they began to take offence, and why Napoleon will continue to divide viewers, critics and historians along national, political and ideological lines. Those reviews may ultimately tell us more about the reviewers than they do about Ridley Scott’s commendable new feature film.

David McQueen lectures in Politics and Media at Bournemouth University and leads the level 6 optional unit: History and Political Struggle: International Perspectives Through Film.

If you would like your interests… published, submit via https://dorseteye.com/submit-a-report/

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/