Dear Cllr Greene,

We naturally welcome BCP Council’s determination to play its part in minimising inessential contacts during this particularly awful phase of the Covid crisis.

However, we feel moved to write to you to express real concerns over BCP Council’s latest social media stay-at-home messaging: “If you go out… you can spread it… people will die”.

We of course understand what you are hoping to achieve, and the seriousness of everyone’s social responsibilities in our profoundly interdependent world has never been greater. However, we have to raise questions over whether your new approach will be beneficial rather than harmful, with the actual positive effect on public behaviour we are all seeking.

There is a considerable evidence base from psychological science suggesting that scary public health messages are far from unconditionally certain to achieve the positive behavioural change that is sought, and can easily backfire.

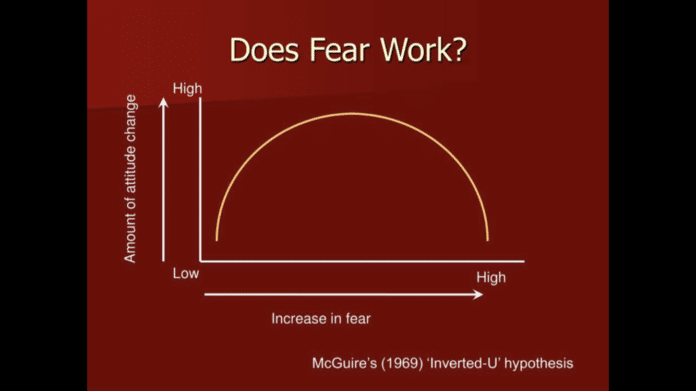

The leading hypothesis in social psychology for understanding the relationship between fear and attitude change looks like this [1, 2]:

That is to say that past a certain point, highly fear-arousing messages are believed to be less effective than more ‘moderately’ fear-evoking alternatives [3]. Humans have mental mechanisms for ‘avoiding’ properly taking in messages, and rationally digesting and feeling them, if they are simply too terrifying to handle, as they go about their busy, complicated and stressful lives. ‘Terror management theory’ [4] suggests we are particularly prone to just batting away overwhelming messages about our own death or mortality. (This is, by the way, why green movements have tended to shift away from pushing terrifying predictions about the climate emergency directly to the general public.)

There is also some scientific evidence suggesting that scary messaging may work, sometimes – if people are helped to understand their own personal vulnerability, and if the messaging offers a non-overwhelming and convincingly achievable way to correct their behaviour. Unfortunately, BCP’s new “People will die” campaign has neither of these essential attributes.

Clearly, it is not possible or reasonable for many, probably most, people to never leave home at this time. Many people are still going out daily to do jobs or volunteering that can’t be done from home, including many key workers. Supermarket deliveries are not readily available, or appropriate and accessible for everyone, with significant proportions of the most vulnerable residents not even online. Many people need to pop to their corner shop now and then for daily essentials. And regular exercise, fresh air and access to green spaces are human necessities for both physical and mental health, a key principle the Government has commendably upheld throughout the pandemic. Many BCP councillors and staff may have the use of extensive home gardens, but many of our most vulnerable residents do not.

Being outside, by yourself, distanced from passers-by and not touching shared surfaces, does not in and of itself spread the virus. It does not, in your new campaign’s terms, cause anyone to die. The Government has little choice but to make its instructions and guidance as short, simple and uniform as possible – but there are inevitably all sorts of exemptions, and in more detailed interviews, ministers including Matt Hancock have acknowledged that the crude rules and slogans do not replace the central importance of individual awareness and common sense regarding one’s risk factors in one’s own unique life.

Anxiety is at its most psychologically toxic when people feel overwhelmed by a problem they feel they have little or no control over. If people feel they have resources to cope and change with an anxiety-inducing situation, it is easier to deal with [5, 6]. Pushing into the faces of nurses who rely on long bus journeys to reach Royal Bournemouth Hospital or Poole Hospital for work that their every journey may cause people to “die” is not doing anything useful for them. It merely further exacerbates their anxiety at the truly harrowing situation they are on the front line of daily. 45% of doctors and nurses based in Intensive Care Units met the threshold for probable PTSD, anxiety or depression during June and July of last year. Anxiety disorders will in many cases degrade people’s ‘Covid safe’ self-awareness in their daily lives, by stripping them of the cognitive resources [7] to be well ‘regulated’ in their physical environment and thus reliably aware [8] of factors such as what they are touching, how far away they are staying from others, their mask staying in place, and so on.

Whether it is your intention or not, it seems highly likely that this campaign will have the effect of shaming some of the housebound people who are severely struggling with their mental health at this time into not going out, in an extremely low risk manner, for exercise and a change of scenery which will improve their wellbeing. The reasons underlying what the country’s top psychiatrist calls our ‘greatest threat to mental health since the second world war‘ of course include Covid bereavement, job loss, isolation, childcare-related stress, reduced physical activity and daily structure, and the toll of ‘long Covid’ cases. Awareness of this, including the potential eventual outcome of increased suicide and self-harm rates, must be a key part of the local authority’s “Covid resilience” response.

BCP’s “You can spread it, people will die” message is so monolithic and lacking in nuance that it actively detracts from what psychology suggests might actually work – helping people to meaningfully understand their own personal vulnerability, so they can take practical behavioural steps to minimise risk. This is more likely to engage some of the minority who have sadly shown over the past 10 months that they do not much care for the safety of strangers.

We suggest what might be a smarter message, both psychologically and epidemiologically, potentially more likely to have a genuinely beneficial effect at this time, along the lines of:

—

If you don’t need to go out, don’t. 1 in 3 people infected with Covid-19 don’t show symptoms, but many of all ages are still dying.

Need to go out? Here are some key tips to minimise the risk of spreading the virus:

- Wash your hands for at least 20 seconds before you go out, and after you get home again.

- Pop some hand-sanitiser in your bag or coat pocket before you go out, and use it frequently while out.

- Take a mask, always wear it in shops and other indoor premises (unless medically exempt)… and it’s a good idea to wear one in busy outdoor areas too.

- Use your toilet before you go out, if it might save you from needing a public toilet while outdoors.

- Take some food and/or drink with you if you might need sustenance while outdoors, so that you don’t have to make an extra visit to a shop.

- If you can, walk or cycle instead of taking the bus or train.

- Stay 2 metres apart at all times from people you don’t live with.

- Exercise with at most one other person.

- Don’t shout or sing close to other people.

- Avoid touching things which other people have touched.

- Try to avoid touching your face.

- Don’t go into shops just to browse, or without planning what you need to buy.

- Remember not to get too close to the worker at non-screened shop counters.

—

For the good of local public health and local Covid discourse, we would like your earliest answer to the following questions:

- What expert advice and/or evidence, from the fields of psychology and/or public health behavioural change, was taken by BCP Council during the process of deciding that this messaging would bring net benefits?

- Was the Public Health department involved in devising and approving this campaign?

- What assessment was made of the potential negative impacts on vulnerable residents, including the many key worker heroes living with significant mental health issues at this time, of the deliberately anxiety-inducing nature of the messaging?

- What assessment was made of the ‘shaming’ potential regarding genuine needs to go outdoors (including legally permitted needs for physical and mental health), particularly for those struggling with anxiety disorders, and the practical mental health impacts on vulnerable residents of any such phenomenon?

- What frameworks are you using to assess the success, and any negative consequences, of this campaign?

- As the social media campaign reported in Saturday’s Bournemouth Daily Echo appears at this stage only to have been run as Facebook and Instagram “stories” which are no longer visible, can you confirm whether the Council intends to run this messaging again?

- If so, and if those involved in approving this messaging were not aware of any of the scientific issues that we have raised, will you undertake to appropriately review the scientific evidence we have cited and reflect on our stated concerns before repeating this campaign?

We look forward to your earliest response. Kind regards,

Chris Henderson BA(Hons) GradDip(Psych) MBPsS – Bournemouth University

Councillor Chris Rigby – BCP Council

Councillor Simon Bull – BCP Council

P.S. The body of this letter is technically oriented, on an issue we would want to remain thoroughly bipartisan, and we hope it will receive consideration by officers. It does however provide context for a secondary ‘more political’ point to be made as this footnote, directed to the Conservative Group.

To whatever extent the ‘People will die’ campaign was politically owned, it’s not the first sign in recent days that BCP’s Conservative councillors may be focusing on some of the wrong points in their public attempts to promote Covid-safe behaviour by all of us. A few of your colleagues have been very keen recently to loudly question certain solo outdoor activity by rivals. We were then a little surprised to note this:

The photo depicts people doing work that can’t be done from home, outdoors, with some effort at distancing – this is allowed by law (whether paid or unpaid). However, it’s unmasked gatherings in groups which most spreads Covid. The risk associated with this photoshoot, although low, looks higher than the “risk” from solo deliveries of post which have been the target of demonstrably baseless recent claims by Conservative councillors. This logical contradiction, added to the real grounds for challenge regarding the appropriateness of the BCP “people will die” campaign, raises questions about whether local Conservative councillors have attained the level of education about the actual science (both epidemiological and psychological) and specific risk factors which the BCP public would rightly expect from their municipal leaders at this time.

Will BCP Council’s Conservative Group commit to assessing the need for urgent education for all its members on understanding Covid protection measures in scientifically rooted terms of (i) actual personal risk factors and (ii) some understanding of effective behavioural change, in addition to just “the rules”?

Academic references:

[1] McGuire, W. J. (1969). The nature of attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (eds.), Handbook of social psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp 136-314). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

[2] Janis, I. L. (1967). Effects of fear arousal on attitude change. Recent developments in theory and experimental research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 3, 167-224.

[3] Keller, P. A., & Block, L. G. (1995). Increasing the persuasiveness of fear appeals: The effect of arousal and elaboration. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 448-459.

[4] Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1999). A dual-process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: An extension of terror management theory. Psychological Review, 106, 835-845.

[5] Blascovich, J. (2008). Challenge and threat. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation (pp 431-446). New York: Erlbaum.

[6] Blascovich, J. & Tomaka, J. (1996). The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 1-51.

[7] Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756.

[8] Stopa, L., & Clark, D. M. (1993). Cognitive processes in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31(3), 255–267.

PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH