Chapter 16

Gainful Employment

‘But George Orwell had something to fall back on. He had money behind him’.

I didn’t want to admit it but I could see that my Dad might be right. Washing up day in day out might eventually get boring.

But what about W. H. Davies? ‘The Autobiography of a Super Tramp’ had been so persuasive. The company of honest souls, straightforward people with simple needs. The dignity and honest fatigue from physical labour, the scholarly volume for secret study stashed inside a bedroll.

This was my own decision though, the first time I wasn’t going along with somebody else telling me what I ought to be doing. How could being an apprentice draughtsman, my Dad’s suggestion, bring any meaningful and deep fulfillment? Guaranteed employment, enforced conformity, marriage to a local girl who worked in a shop. Fifty years of that!

I told my father that I wanted to be a tramp, an intellectual one. I could so clearly imagine myself at reading tables in public libraries, working my way methodically along the stacks. I would be warm and dry. I wouldn’t want for anything more. And I would learn infinitely more than I ever could from grinding on through a final year with ‘A’ levels.

‘And where would you sleep?’

‘In hedges and fields. Wherever I ended up that night’.

‘Don’t talk so wet’.

But it must be possible. Davies and Orwell had managed through the storms, the rain and the snow. Had written the books to prove it. All it needed was some of the initiative that school and my Dad were always on about – the officer material stuff, the leadership potential. But not in the service of Queen and country, respectability and a soulless life. In the pursuit of poetry instead, philosophy, the camaraderie of the trail, the grit, grime and freedom of voyages without destinations.

*

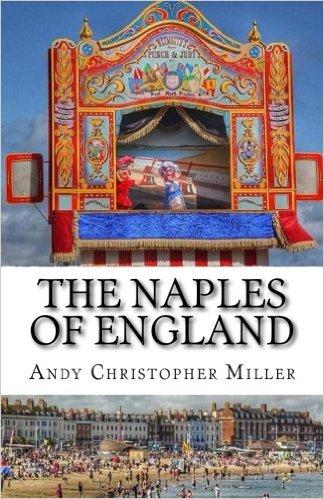

South Dorset Gazette 22nd June 1964

‘Mohairs’ get a welcome cuppa

Weymouth has always been famous for its record numbers of summer visitors. But this year a new group of arrivals has set local people talking.

The ‘Mohairs’ – so called because they have ‘more hair’ than the average person – are a group of young people who arrived in the town in May after being cleared out from St Ives, Cornwall, following a purge by the local town council. There are some 15 to 20 of them currently here but the town has been warned that many more could be expected if the word gets around that Weymouth offers them a warm welcome.

Pictured enjoying a cup of tea at the Early Bird Café on Park Street is Mohair Sammy Easterman, 20, originally from Birmingham. He is currently looking for temporary holiday work and says he will consider anything, from lavatory cleaner to bank manager. He adds ‘It’s a free country and we just want to live our lives in the way that we want to’

Also pictured is Albert Watts, proprietor of the Early Bird cafe.

‘A lot of people don’t like the look of the Mohairs, but they should take the trouble to get to know them. Under the surface, there are some very nice young people here and they will always be welcome in my café,’ Mr Watts told the Gazette.‘Older people only think about material possessions and mortgages and things,’ said Linda, another Mohair from the West Midlands, who did not want to give her age or surname.

‘Weymouth is rightly proud of its reputation as the ideal holiday resort for families and people of all ages,’ said Cllr Frederick Watson, Chair of the Tourism and Leisure Sub-committee of Weymouth Town Council. ’We have been placed in the top ten British seaside towns for the past five years running. The Council will be monitoring the situation with these young people very carefully,’ he told the Gazette.

___________________________________________

*

In late July that summer, I obtained a job in the kitchen of the Solent Hotel up on the seafront. On my first day, I was shown around, my basic duties were explained and I was set to work to pull up the dishes from the floor below by means of the dumb waiter. In the open lift shaft, the top of the wooden case creaked upwards only minimally despite all my pulling and I wondered whether I had the strength for the job.

‘Here, let’s give you a hand,’ said one of the kitchen staff and, with him also pulling firmly on the rope, we managed to raise the contraption further. Our final attempts lifted the open fronted box up to the level of the hatch. But, instead of plates, compacted inside and inches in front of me, knees up to his chin like a foetus and with a long kitchen knife between his teeth, was a wild-haired, mad-eyed homunculus. It was Sammy, the Mohair whose photograph I had seen in the newspaper. When others had eased him out, he ran about the kitchen, bent at the knees, the knife now waving in the air.

The others stood back to allow his manic passage as he slashed at the air mimicking a crazed pirate. After a circuit of the central aluminium storage unit with the others laughing but allowing him a considerable berth, he stopped right in front of me. Still crouching low, he turned one eye upwards. It seemed bulbous beneath his spectacles and somehow swollen larger than the other.

‘What brings you here? Are you friend or foe? Answer for your life!’

I struggled to match the mood and find the words, unsure whether I should speak at all. Then the swing doors to the corridor burst inwards and a tall moon-faced man entered, stiff legged and swaying slightly from side to side. He was dressed in a gold lame suit and wore a large stetson hat. His hands were making circular movements as if twirling six guns.

‘Just back off from the boy and put down the knife,’ he drawled.

The laughter intensified, splitting into an echoing gaggle of shrieks and yells.

‘Come on, I’ll show you what to do,’ said a quieter man in a brown T-shirt and denim jeans. ‘I’m the other washer-upper, Billy. Don’t worry, they do that to all the new people, it’s nothing personal’.

‘We have a laugh here,’ he added. ‘Most of them are alright. Just one or two you need to look out for’.

I was introduced to the first laugh early the next morning in the rush to prepare breakfast for some eighty guests. Sammy, still an unpredictable character, shouted from the bank of gas rings near the serving surfaces, a raised sticky ladle in his right hand.

‘Porridge is ready!’

‘Come on, get in the queue,’ said Billy as people lined up beside the large cauldron of molten porridge that burped and belched occasionally in the pan.

‘Okay,’ said Sammy. One of the waiters was first in line and he came forward, bent over the pot and pretended to spit into it. One by one, kitchen porters and waiters stepped up beside Sammy, acknowledged his lop-sided grin and made their donation to the pot. I was trapped and had to comply as they all watched me, the new boy. I gave a limp imitation, nothing compared to the exaggerated hawking and retching of some who provoked squeals of appreciation and mock disgust, but I seemed to pass the test.

‘I can’t see what’s so good about a crowd of layabouts,’ my Dad said when I enthused at home about my new workmates.

‘But they’re real people, Dad,’ I complained. ‘Billy’s even been in prison but he’s really kind. And genuine’.

‘Genuine? You want to watch yourself or you’ll end up in the clink with them’.

One morning, after I had been at the Solent for a week, one of the younger waiters approached me in the corridor.

‘Are you the grammar school boy who’s working here?’ He spoke in the broadest Irish accent I had ever heard. ‘What do you study?’

I told him it was maths and physics but did not mention my disappointing GCE results and the fact that I had only just scraped into the sixth form.

‘No philosophy, no literature?’ he fired back. ‘Do you study Plato? Euripides? And what about Irish writers? Shaw, Wilde and Yeats?’

‘Our school doesn’t do philosophy,’ I replied ‘but I have done a bit for myself’.

‘What? What did you read?’

‘I got Gilbert Ryle’s ‘A Concept of Mind’ out of the library last year’.

‘What did you think of it? What struck you the most about it?’

‘Well, I didn’t read all of it, mainly the first few chapters. I remember it was something about what’s real and things. About perception and stuff’.

‘Huh. Metaphysical ramblings. You need Joad, ‘An Introduction to Philosophy’. It’s a ‘Teach Yourself’ book. It’ll get you started. And literature. Shaw’s ‘Man and Superman’ probably. And what about Thoreau? ‘Walden’. You must read that straight away, before anything else. Oh, and Colin Wilson, ‘The Outsider’.

My new personal tutor – there had been no opportunity to decline the rapidly lengthening reading list – was called Bernard. He was only a couple of years older than me and dressed conservatively in dark trousers and a long-sleeved white shirt. He had dark hair, already slightly graying and combed sideways with a cartoon-like set of rippling small waves. He and his friend Nick had come to Weymouth following the clear out from St Ives earlier that summer. Their plan was to move on at the end of the summer season to spend the winter in London and then the following spring in Montmartre where Bernard intended to settle as a full-time painter.

After my first pay day, Bernard came with me to W H Smiths where we presented a list of books to an attractive girl with long blonde hair who had been in the year below me at school.

‘We don’t have any of these in stock but we can order them for you,’ she said, giving no indication that she recognised me as she consulted a large, well-thumbed catalogue.

Bernard advised which should be asterisked as priorities. The assistant remained immune to the list’s aura of gravity.

When the books finally arrived I decided to tackle Thoreau first, drawn by the title and even more by the tone of rebellion in the title of the final extended essay, ‘On Civil Disobedience’. The text was dense and there was no respite in levity or short, snappy sentences. But I was determined that this was to be a period of study unlike all those before when my attention had rushed in every direction except along the lines of a text book’s printed sentences. This would not culminate in another humiliation stretched across slow, silent hours in an examination hall.

‘I’ve never read anything like this before,’ I said one day at home of Joad’s ‘Introduction to Philosophy’. It makes you question everything, everything you’ve just taken for granted’.

‘Don’t read it then if it’s upsetting you,’ said my Mum. ‘Read something else instead’.

‘It’s not upsetting me. It’s the most amazing – ‘

‘It’s a pity you can’t show the same enthusiasm about something that might actually help you get a job when you leave school,’ interjected my Dad.

I held back a furious desire to scream that the human race could never hope to improve itself in the face of such … such … I didn’t know what.

Over the next few weeks, Bernard and I occupied ourselves with our books in between shifts, first in the Early Bird Café and then, when the proprietor announced that he was banning ‘low-life’ from his premises, tucked away at the back of Fortes Corner House in the centre of the town. Bernard would open his creased and battered copy of the volume under consideration to reveal sections of ink and pencil underlining. Never before had bookish analysis possessed such dramatic import for me, – the writer as revolutionary, the reader as acolyte. I lost myself among outsiders, wanderers and seekers and left my former school friends to their bars and dance halls. My ignorance and lack of application were revealed by questions that I now longed to be able to answer.

‘What are the deep themes?’ ‘How does the author bring home his argument?’

I also took to underlining as I read and my pages were soon extensively scored with only occasional passages left white and unmarked like glimpses of accidentally revealed flesh.

Returning home one night after a dizzying extended tutorial spent scrutinising the preface to Shaw’s ‘Man and Superman,’ I found Uncle Sid sitting with my parents in the living room.

Both my parents spoke of Sid with an unqualified affection. He worked as a gardener and wore checked open-necked shirts, a slowly weathered tan and a wide smile. When a meal was placed before him he looked down at it in silent pleasure as if saying a personal grace before starting to eat. When beckoned to an armchair in front of the television, he approached it with what seemed a glowing and genuine gratitude.

Somehow that evening I found myself quickly on from stilted pleasantries.

‘But if I’m looking at something, this tomato for instance, and I’m seeing what I think of as the redness of it, what I’m really seeing is rays of light coming off this thing and striking my eyes which then get transmitted to my brain and that sensation in my brain is what I call the redness’.

Sid seemed to be following, his head was bent forward slightly.

‘Now, what we don’t know, is whether exactly the same is happening in your brain. You’re getting your own rays striking your eyes which are then going through to your brain and creating what you call redness. But what we don’t know, is whether your redness is the same as mine. How can we? We just assume they’re the same and we use the same words but that doesn’t mean that anybody’s experience of redness is the same as anybody else’s. We have absolutely no way of knowing’.

‘Well, I don’t know, Andrew,’ said Sid. ‘You make it all sound so complicated. All I know is that that tomato is red, that’s it really’.

‘But that’s my point. You don’t know that! Well, you don’t know that it’s the same as what I call ‘red’’.

Sid looked even sadder and my father quickly intervened, silencing the evening.

‘He’s going through one of those phases,’ he said sharply. ‘Reading Bertrand Russell and what have you. They all go through it’.

Chapter 17

Above and Beyond

At 16, I joined St Mary’s church youth club down among the tightly terraced houses near the railway station, not to find God but to meet girls.

I had given up on religion a few years earlier after regular stints of Sunday school and church at St Oswalds, nearer my home. When I had complained about this enforced attendance, which I felt marked my brother and I out from all the other children on the Shorehaven estate, my mother always said I could decide for myself when I was thirteen. Apparently this was my father’s stipulation although I had never actually known him to enter a church. On the stroke of my designated spiritual maturation I consequently made a rapid departure.

My mother arranged flowers in St Oswalds and washed the altar steps. Glimpses of the curate, Father Schofield, floating through the vestry replenished her emotionally whilst also agitating her compassion beyond its easy or comfortable expression. He was a tiny, fleshless man, sometimes seeming little more than a loose collection of bones somehow held together beneath his cassock. He had been a Japanese prisoner of war my mother informed me. And as I watched him move silently among his rituals, I tried to imagine the squalor and the blows that might have been inflicted on him in the wet heat of a jungle camp.

Father Schofield’s humility and dignity suggested that he had found a balm for his wounds and I knew that he would remain in my thoughts. But otherwise I felt only relief at getting away from the stifling respectability exuded by his superior, the vicar, a well-fed career clergyman who preached cloying and clichéd sermons and presided over sickly summer fetes.

My friend, Dick, told me that the girls at St Mary’s youth club were less restrained than our grammar school contemporaries but that the price to be paid for access to these temptations was the mid-evening coffee break. At around half past eight, Bob, the young curate who ran the club, began scraping the wooden chairs back into rows, barring the clanking, heavy exit door with no more than a keen eye and a chilling charm. The tap and cluck from the table tennis room died away and we sat, avoiding his glance, beneath the buzz of a yellow strip light while Bob dispensed spiritual guidance for the regulation fifteen minutes.

Wearingly-familiar Bible stories gained some lift, however, when Bob forced them into the world we tried to claim as ours. Frank had been coming to know the Lord, he told us, he really had, in the days before his huge Norton roared from the road splintering a row of fence posts before its fatal impact with the telegraph pole. And the evening the snooker tables crashed onto their sides and the billiard balls ricocheted and whined against the tiled walls and flagstone floors, Bob strode between them parting the sea of missiles. He halted hostilities by dragging out a large, dusty gymnasium mat, as brown and bristly as a fox. ‘Queensberry rules chaps. No punching or biting, no knees and no hitting below the belt’. First he took on one ringleader, circling in an almost polite fashion until the first engagement, the assault on balance, the thud of bodies against the floor, the assertion of strength and the weakening in one shoulder and then the other. Afterwards, blood, sweat, spittle and torn clothes with Bob extending a handshake, wiping his mouth and then turning to repeat his challenge to the other gang leader.

No milk and water respectability this. No Holy Joe, genteel and practised among his catechisms.

Bob could not have been more different from the clergy I had known at St Oswalds. His curriculum vitae was transcribed directly from the adventure stories of my childhood – public school, Cambridge, the Marines with whom he had crossed the Sahara and become a rock climber and mountaineer. Divinity college. Not one glimpse of any such experiences in all my years growing up in Purbeck Road, nor across the whole of the Shorehaven Estate. My friend Dick and I became willing recruits as seconds on the rope as Bob explored the untouched sea cliffs at Lulworth Cove and Portland. We were conscientious students in matters of the waist belay and bowline, the three points of contact with the rock, the careful footwork and the superiority of balance over brute strength.

He sparred, to my delight, in the correspondence columns of the South Dorset Gazette with Mr Price, the local coast guard: sheer irresponsibility, treacherous terrain, endangering others versus the spiritual need for unimpeded adventure, the full exploration

of one’s limits.

The thrill of debate, the ripostes and the counter-arguments.

over-stretched rescue services, the duty to set an example

clashing directly with teamwork, skills chiseled during disciplined apprenticeships, the testing of character.

I had always avoided clubs and organisations designed to deliver a disciplined experience of adventure to young people. The enthusiasts for the Scouts I had known in my younger years seemed most often to be the boys with a profligate strength, the fighters. The later enthusiasts for the Duke of Edinburgh award, on the other hand, were the supporters of order and leadership, of Queen, country and the responsibly-constructed outdoor latrine.

Perhaps it was the daily expounding of my father’s too ready support for his wartime experiences in the RAF, the imposition of a firm military order giving him the best days of his life. Or maybe it was my mother’s unhappy experiences with the various church clubs and societies she enthusiastically signed up for only to scurry quickly away after some early tiff or altercation with another of their members. But whatever made me wary and suspicious did not apply out on the cliffs.

Standing with Dick on a small ledge above a sullen, restless sea on one of our first trips, no escape but upwards, I could hear Bob above us hammering in a piton that would provide a secure anchor for the three of us, his voice booming in full song and the blows of metal on metal providing cold chinks of accompaniment.

‘For – those – in – thwack – per – il – thwack – on – the sea – thwack’.

Here was adventure devoid of the smothering oversight of institutions. No packs, or troops or gangs. High stakes on walls of sea-scoured limestone. No hierarchies, no accrediting bodies, the only disciplinary forces, God and gravity.

Only in his mid-twenties, hospital visiting and a subsidiary role at evening service were insufficient to keep Bob in Weymouth and he was away within a year or so to the new challenge of running a Boys Club in Bermondsey. A year later, aged seventeen, Dick and I hitched there. Along the line of shuttered warehouses down from Tower Bridge at night, Earth had not anything to show more menacing or more frightening. In an empty light early the next morning, the city already in motion along its streets and river, we each requisitioned a best fit set of equipment from the club’s store room – boots, anorak, sleeping bag and inflatable mattress – and set the compass further north, the furthest in this direction ever for me, to the recently opened M1. On this superhighway we took account of the complex new regulations my father had warned me about. ‘Apparently, once you’re on it, that’s it. You can’t change your mind and turn round’.

Running in his new yellow Ford Anglia at speeds never in excess of forty miles an hour, we were heading into thinly sketched mountain marvels. The fourth member of our party was Eric, a young man probably no more than ten years our senior, whom Bob had first met as a regular inmate on his rounds of visiting at Dorchester gaol.

After a whole day, we arrived in Snowdonia. Driving through the Nant Ffrancon Pass, looking for the track down to our barn, massive hillsides rose in slides of scree and rubble above the single road. Buttresses of the deepest Celtic green, rough ground tumbling out of the mist and down to the valley floor, these were landscapes beyond anything I had ever imagined. Our base – our lives – for the next week.

Eric’s eyes followed another waterfall upwards, its source hidden in the sky.

‘Thuck-in nell, Bob. Look at those bath-tuds’.

Silence from the driver. Mortification from the other passengers.

‘Caw, thuck me!’

‘Eric!’

‘Nnn?’

‘The ears, Eric. Getting a little red’.

‘What? Oh! Oh, thuckin nell, Bob, thorry’.

All week heavy mist, cloud and rain dominated the valley. Each morning this weather made its insolent parade around and between the isolated farm dwellings and the bluffs of inhospitable ground. In the barn, we attempted to prepare meals over primus stoves, the smell of the meths never completely absent, the pans never fully free from the burned-on remnants of our previous efforts. Bob modelled orderly living among the privations. Each evening, after soakings and exhaustion on the hills, he led a session of prayers accompanied by mugs of cocoa. Nobody dared raise the possibility of a lift to the village pub.

On our final day, we attempted a rock climbing route on Lliwedd, a mountain composed of north-facing cliffs and buttresses. Some years later, when I met a wider circle of contemporary climbers, I learned that this abandoned place had once been a favoured haunt of that generation of pioneers from the 1920s and 1930s, men with a vanished ethic of risk and hardship.

We were only two or three rope lengths up the route, about two hundred and fifty feet, and I was standing alone in snow left over from the winter on a tiny ledge, when the exposure took a grip on me. To either side, un-climbable walls thinning out into nothingness. The line by which we had just ascended disappeared quickly into cloud beneath our feet. Improbably steep rocks above looked just passable, at least for the few feet into which visibility extended. As soon as somebody climbed into the mist, their voice was snatched away by the sideways buffeting of the wind. Out of contact, except for the wet rope around my back and wrists, the void in front and beneath, the hopeless features of the rock walls all around, I was incarcerated on this tiny, snowbound stance, held in by emptiness and despair.

As my turn to climb again arrived, my resolution dissolved into the vast indifference of the landscape, the dripping rock pillars, the patches of stale snow, the grey tumult above, below and to my sides. There was the best part of another thousand feet of this, continuing upwards, further and further from safe, solid ground. I was already shaking before the needles of cold again began to probe each point of entry into my clothing, shivering at the lost hope of ever feeling safe again. Part of me wanted to jump, to untie my waist belay and cast free, to end the accumulating sense of hopelessness. Part wanted to blame Bob or kick at the rock and withered heather. I could only just bite back the adolescent howl that said I wanted to end it all, a howl that nobody would hear.

When I reached Bob he was hunched up against the weather, bringing in the rope, and still smiling.

‘I’m sorry, Bob. I can’t …. I just don’t think I can …’

‘Don’t worry, Andy,’ he shouted against the buffeting wind, although he was only a couple of feet from me on our tiny belay ledge.

‘You can do it. God loves you’.

Next week the final three chapters:Concrete Proposal, As Long As Everyone’s Alright and Neither Shape Nor Shadow

If you would like to buy the book click here.