In the aftermath of Labour’s phenomenal performance in the 2017 General Election, Tony Blair called on Jeremy Corbyn to return Labour to the centre ground or face political wilderness, warning of the ills of “unreconstructed hard-left economics.” However, Corbyn used his 2017 New Years’ message to proclaim that Labour was “stalking out a new centre ground.” What is this lucrative centre ground, and who has the key to capturing it? Is it Tony Blair, whose quest to capture the centre led New Labour into a triangulation of twenty years of Thatcherite politics, or was it Jeremy Corbyn, whose manifesto of nationalisation and redistribution and commitment to peace transformed the nature of political debate in Britain? Does the centre ground even exist?

A very important comparison can be drawn between 2017 and the 1945 general election, in which Labour won its first ever majority. Long the orthodoxy among historians, Paul Addison’s contention that “consensus fell, like a branch of ripe plums, into Mr. Attlee’s lap” has seen the post-war period treated as a time of agreement between political parties in which debate was constrained within parameters that were set by the wartime coalition: a mixed economy, the priority of controlling unemployment, and a welfare state were the main areas of convergence. Is this the fabled centre ground?

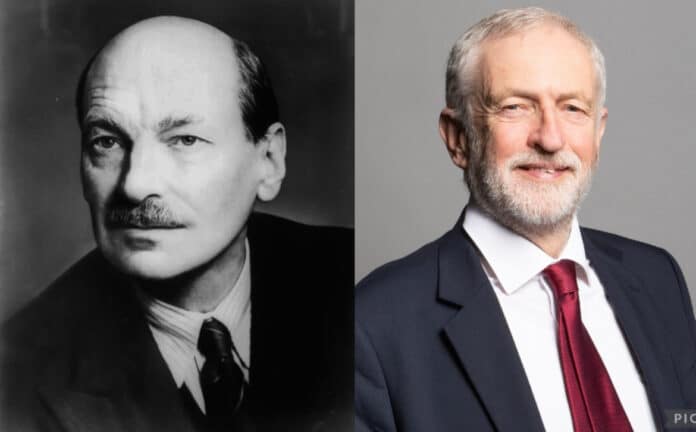

Not according to Winston Churchill. During the 1945 election campaign, Churchill made an explicit comparison between Labour and the Nazi Party by stating that a Labour government would require “some form of Gestapo” in order to implement its programme, only weeks after Belsen had been liberated. Similar smear tactics against Corbyn clearly affected Labour’s performance before the general election, but in June 2017 over 40% of the public voted for Labour—people who obviously did not take completely seriously the claims that Corbyn is a threat to national security. The fact that the public largely rejected the claims that Corbyn and Clement Attlee were hard-left extremists suggests that their politics were far closer to the views of the average person than those of their right-wing detractors.

The assertion by many historians that all politics was conducted from the centre in 1945 is not evident in Labour’s domestic policies. While the Labour governments set about nationalising vast swathes of industry, the Conservative manifesto summed up emphatically in favour of the free market, arguing that “Nationalisation involves a state monopoly, with no proper protection for anyone against monopoly power. Neither that nor any other form of unfettered monopoly should be allowed to exist in Britain.” While maintaining nationalised industries such as coal and rail, the 1951 Conservative government privatised the steel industry. Evidently, the Conservatives had been forced into accepting a settlement that they were ideologically opposed to since it aligned with the majority of public opinion.

The “unreconstructed hard-left economics” that Tony Blair has warned of bears a lot of resemblance to the policies that won Labour a landslide in 1945. Despite the attempts to portray Corbyn and John McDonnell as unpatriotic Marxist extremists, these economics are firmly within the boundaries of Keynesian management theory. And they were popular: 53% of people in a 2018 YouGov poll said they supported the nationalisation of energy companies. Nationalisation is now back on the agenda, and like in 1945, Labour has made the argument popular again.

Aneurin Bevan led the Labour government towards creating the NHS in the face of opposition from the British Medical Association, which was backed by the Tories. Although concessions were made to allow private patients, Labour’s NHS was a dramatic step towards universality of provision. Labour’s own wartime policy, outlined in the 1943 publication ‘A National Service for Health’, did not advocate nationalisation of the hospitals. Instead, wartime Labour and then the Tories and some members of the 1945 Labour government supported a tripartite system that preserved voluntary and charitable hospitals. However, Bevan referred to these voluntary and charitable hospitals as an important source of ‘political and social patronage’ for the Tories and pressed ahead with nationalisation. The principle of charity, where welfare is voluntary and totally dependent on the kindness of individuals, is alien to a socialist system, and if it were not for Bevan’s efforts, it might have been the basis of our health service today. The NHS is phenomenally popular and perhaps the most enduring achievement of Labour; so popular that these days the Conservatives have had to resort to privatising the system under flowery language such as ‘Accountable Care Organisations’, all while proclaiming their love for nationalised health care.

It would be a positive step towards defending public health care if Labour were to lend their full support to an NHS reinstatement bill, as Corbyn, McDonnell, Abbott, and others have done in the past. Since the public is overwhelmingly in favour of public healthcare (83% favoured nationalised healthcare in the 2018 YouGov poll), it falls upon Labour to make the connection between the public’s desire for nationalised health care and the reversal of decades of privatisation.

Where the left is most disappointed by the 1945–51 Labour governments is in foreign policy. Many prominent left-wingers were placed in domestic departments—Bevan had both housing and health—whereas those on the right of the party were given foreign policy roles. As a result, Labour’s foreign policy accepted the pro-American orientation of the post-war world. Opposition to American dominance came from the Labour left, with Michael Foot, Barbara Castle, Jennie Lee, Seymour Cocks, Raymond Blackburn, and a dozen other Labour members voting against America’s multi-billion-dollar loan to the UK, which entailed commitments to NATO. Although there were some differences between Labour and Conservative foreign policy, most notably on Indian independence, the efforts of some Labour MP’s to create a socialist foreign policy failed. Jingoism prevailed, and Britain developed its first nuclear weapon. Ernest Bevin summed up the mood among the Labour leadership: “We’ve got to have a bloody Union Jack on top of it!”

Jeremy Corbyn’s lifelong commitment to peace set him apart from the majority of the PLP like no other issue. Although Labour’s 2017 manifesto remained committed to Trident and the 2% of GDP military spending target, there was a moment during the 2017 election campaign that turned the whole debate around foreign policy on its head and, in many ways, summed up the Corbyn project. Straight after the Manchester terror attack, Corbyn delivered a speech that highlighted the role that British foreign policy in the Middle East plays in fostering terrorism. It is totally unconventional for an opposition leader to deliver a political statement on such an issue. If the press and right-wing politicians were to pick a moment to deliver their fell blow and brandish him as a terrorist sympathiser forever, this would be it. Yet Labour’s poll ratings continued to rise. Jeremy Corbyn continued to demonstrate the merits of an anti-war foreign policy and dispel the myth that wars win elections.

So whose model of the centre ground works best? Is it Tony Blair’s assertion that elections are won by agreeing with your opponents on most major political questions, or is it Jeremy Corbyn’s appeal to the many by putting out a distinctly redistributive platform? Labour won a landslide in 1945 by disagreeing with the Tories. If we are confident in our left-wing beliefs, then we should be promoting them without hesitation. What Labour proved in 1945 and proved again in the aftermath of the 2017 general election is that the centre ground of public opinion is malleable and responds to political arguments. Tony Blair’s impression that centrists are above left-right politics—that they don’t stand for anything—is disingenuous. A centre ground of politicians who go a third way on essentially binary issues such as public or private does not exist; all must take sides. And increasingly, these so-called centrists are being proven out of touch with a newly febrile public opinion.

The socialists in the Labour Party who remain must continue to resist all efforts to return the party to Blair’s centre ground. However, given that so many have been expelled on trumped-up charges, this looks extremely difficult.

Charlotte Austin

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/