My first attempt at writing one that gave the reader a warm fuzzy glow, the feel-good factor, full of Christmastide cheer, had somehow ended up instead laden with the doom and gloom of death, drunkenness and debauchery!

As I frantically scanned the newspapers each successive year for the Christmas period, they seemed to be filled with nothing but peoples misfortunes and misdeeds…but I guess that’s what always sold, and in fact still sells newspapers.

I’ve finally settled on the year 1862, and though it might not be overly full of that golden fuzziness I was after, hopefully it contains a bit more of the good old Christmas spirit.

It was the Victorians who really started those traditions that are now firmly established with our present-day Christmas, or rather can be put firmly at the feet of Queen Victoria’s German born husband, Albert.

Though originally their festive season was far less commercialised than our own, with the arrival of the industrial revolution, it pretty soon burgeoned.

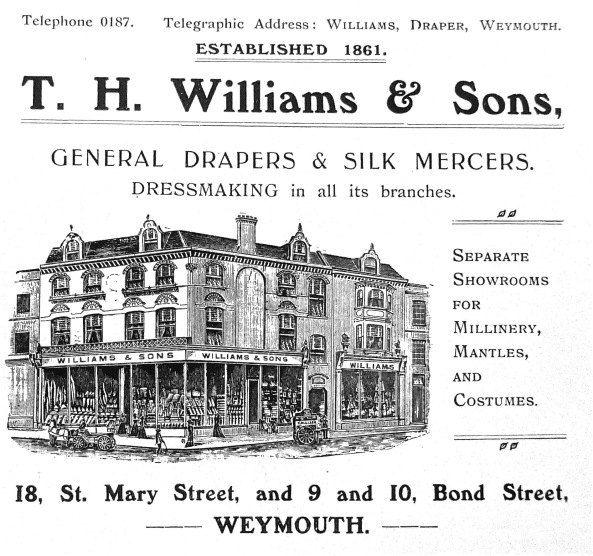

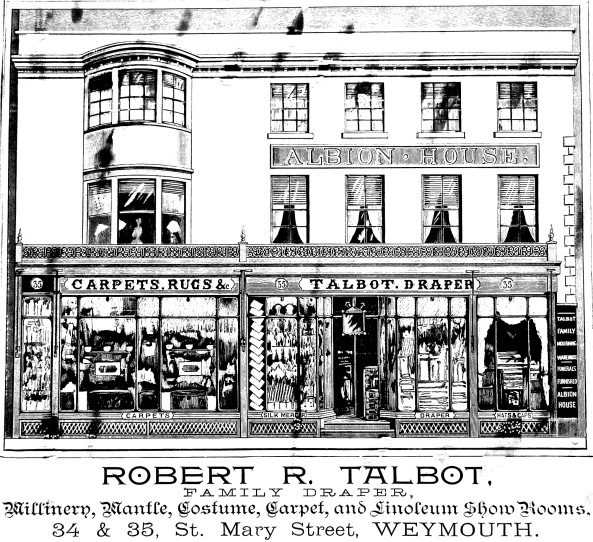

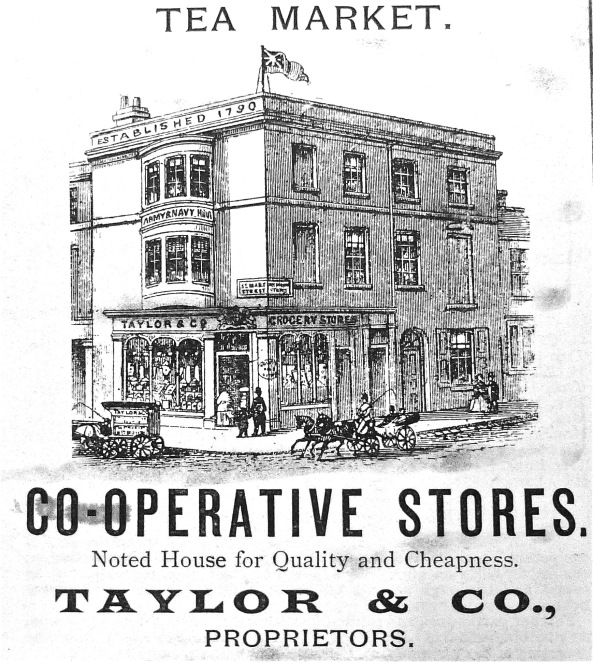

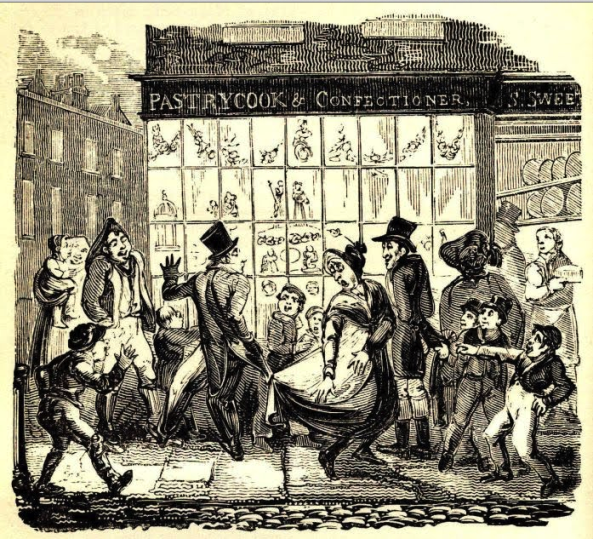

Mass produced goods started appearing in the numerous grand department stores and little shops that lined the main shopping areas and Weymouth could boast many a fine store.

L725-213. MA8; 1905.

Good laden stores such as T H Williams & Sons and Robert Talbot’s on St Mary Street…

…even a good old Co-operative store, run under the name of Taylor & co, noted particularly for its ‘quality and cheapness.’

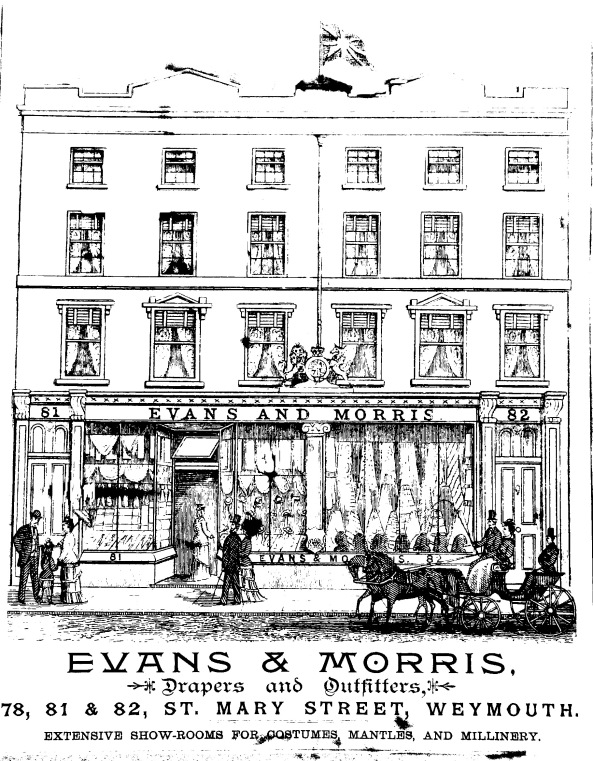

Further along St Mary’s Street stood the premises of Evans & Morris.

Note the impressive royal crest above their windows and the patriotic flag flying on the rooftop!

As Christmas approached their windows would be filled with all manner of glorious gifts for those you loved, from brightly coloured toys and soft kid gloves, to silver topped walking sticks and dapper hats.

Children from all walks of life must have pressed their runny noses against the cold panes of glass, as they peered in those windows full of glittering promises and dreamed of the possible delights to be unwrapped come Christmas. (That was of course, supposing their family could afford such luxurious.)

For many children of the town though, it was to be nothing more than an orange and a few nuts if that.

But renown for their industriousness, many would spend months before beavering away making little gifts for their friends and family.

I can just picture one of my young ancestors curled up on her chair of an afternoon, making the most of the remaining daylight streaming in the window, (here I am perhaps rather idyllically assuming that my ancestors were of the wealthier variety.)

She is carefully and lovingly embroidering a delicate linen handkerchief for her dear mother. Her pink rosebud lips pursed in total concentration as the shiny needle continues weaving colourful stitches in and out, the merest of smiles softens her face as she contemplates the expression on her mother’s face come present unwrapping time.

Or maybe she’s working a small cloth for her beloved grandmother, one that can be placed on her bedside table.

But trade being …well, I guess, trade, Victorians were quick to spot a lucrative market at Christmas time and soon advertisements began to appear in all the local papers.

So it was for the Weymouth shops and businesses.

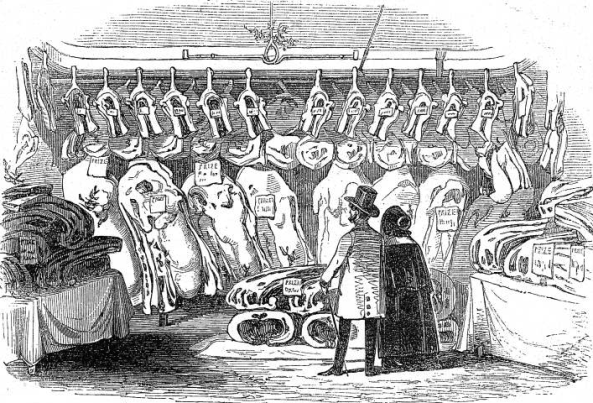

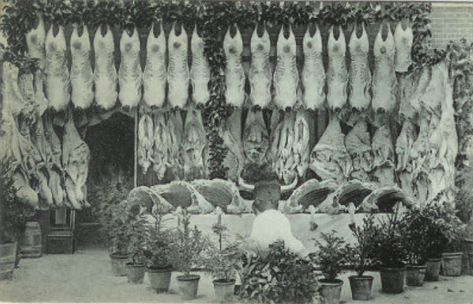

According to the Dorset County Chronicles of December 25th 1862.“The Christmas Show of Meat; in accordance with time honoured custom, the butchers of Weymouth made a public display of their provisions for the festivities of Christmastide on Monday evening, and certainly on no former occasion have they exhibited greater liberality and judgement in catering for the tastes of their customers.”

Old Weymouth alone could boast three butchers to supply the hungry population over the old Weymouth side of the harbour.

Trusty Thomas Norris with his premises in Salam Place (which apparently used to be somewhere near Hope Square.)

Then there was 59-year-old Robert Baunton and his wife Mary Ann who ran the shop along the North Quay. They raised much of their own stock and were frequent winners at the local agriculture shows, a feat that many a 21st century foodie would brag of nowadays.

Last but not least, Benjamin Parson could be found trading his meaty wares on the main High Street.

All would have hung great carcasses of beef , pork and mutton inside and outside their premises, rows upon rows of poultry, geese, duck and chickens would decorate the shop front, all designed to entice in customers.

Cross the town bridge and enter Melcombe Regis, where you could find butchers galore. In fact if you walked down St Edmund Street, it was virtually wall to wall butchers. This was probably a hangover from when this area around the present day Guildhall was actually a designated market place.

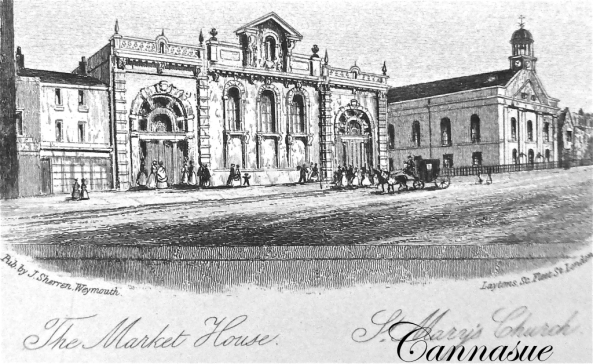

Before the reign of Victoria, outside the old Guildhall once ran a covered walkway for the market traders of the town.

When the new Guildhall was opened in 1835 these sellers were then pushed out, relegated to mere open stalls in the dusty street.

Not only were the traders unhappy with their lot, many residents complained that they were noisy, untidy and ruined the the area.

Consequently a new market hall was purpose built for them in St Mary Street which opened in 1855.

(Not that the traders appreciated this, they said it was cold and unpopular with their customers.)

However, those Victorians out shopping in Melcombe Regis for their festive fare in 1862 could still take their pick from the many trading butchers of the time.

Situated right next door to the gaol in St Edmund Street was the premises of Phillip Roberts, he was aided and abetted by his faithful wife Ann and their 20-year-old son William.

Next door you’d find William Bond and his wife Jane, like many meat purveyors of the day, they are specialising in pork butchery.

Thomas Stickland and wife Christian work the meat counters of the next shop along. Here they “exhibited three serviceable heifers…” Beef wasn’t their only offerings, “He also had at the will of the public several prime down wether sheep…” last but not least the duo also advertised “some choice Portlanders, grazed by himself.”

Many of the butchers seemed to have raised their own small flocks, especially of the Portland sheep, for the Christmas period.

Then we have Daniel Stocks, master butcher, and Rachel his wife and their assorted brood.

Finally, you have the grandaddy of all Weymouth butchers, Edward Baunton (& Sons.) Edward was widowed by the 1861 census, but that’s not a problem as far as his business is concerned, he has his whole family helping him.

From his 36-year-old daughter Jane, his two sons, Edward and John, his teenage grandsons, William and John right down to various live-in butchers assistants, they all worked in this thriving butchers shop.

Christmas, of course, was their busiest time, and it’s when they really went to town with their displays.

Such things were noted in the local papers on the build up to the festive season, including, oddly enough, where their stock had been raised, where it grazed, what awards it won.

Brings the true meaning of ‘from hoof to home.’

“The impromptu bower of evergreen over the pavement and the crescent-like form of the show of meat in the interior of the shop, with the display of the honourable trophies personally received by Mr. Braunton snr,and those awarded to the animals, proved that those who had arranged the display had an eye to effect-anxious to please the eye as the appetite.”

Turn into St Mary Street and here you’d find that the men of meat also literally ‘hung together’ so to speak.

Starting off with 40-year-old Alfred Bolt and his wife Margaret at no 60.

Even though they were a only small business, Alfred “exhibited some good ox and heifer beef from the herd of Mr. E Pope Esq. of Great Toller…”

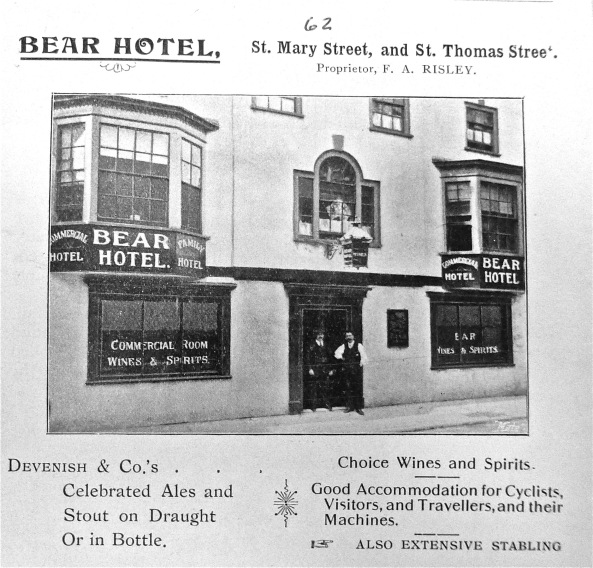

Next came John and Susannah Sanders at no 64, this stood next to the bustling Bear Hotel.

Their son Henry worked alongside his parents. According to the reporter “his show of beef appeared to us the acme of perfection.”

Then there was the Dominy family at no 66. Father George, his wife Mary and their sons John and Henry who worked behind the counter. Even their youngest son, 8-year-old George would have had his chores to do.

Living on the premises with them were a bevy of servants and butchers assistants, a busy household for poor old Mary to run and look after.

But good old George was a wily trader, he catered for everyone, “His show was alike serviceable to the rich and the poor.”

This family also ran a butchers shop in Park Street, “though perhaps not so well situated for attracting the nobility.”

William Lowman was the last man standing in this line of meat purveyors at no 69.

Well, in fact that’s not quite true.

William was actually the borough surveyor, it was his wife Sarah who was the trader, a poulterer, (birds to you and me…) and the rest of his family worked alongside their mother, Sarah jnr, Joseph and William.

Those muscly men of the meat trade in St Thomas Street preferred to keep their distance from each other.

Thomas Walters and wife Mary were pork butchers at no 1, and right down the other end of the street was Henry Billet, and of course his wife Mary another pork butcher at no 52.

That wasn’t all.

Even Maiden Street could boast two butchers, Edward and Eliza Townsend at no 7, and perhaps rather aptly named young kid on the block, Joseph Rabbets at no 18, and of course not forgetting his beautifully named wife Emily Virtue. The young couple must have raised their own flock of lambs for “The Portland sheep were A1, and of his own feeding.”

George Pitman was tucked away in St Albans Row while Frederick Hatton traded at no 4 Bond Street.

Butchers of course weren’t the only shop keepers hoping for a bumper Christmas and the joyous sound, the merry ringing of the cash registers.

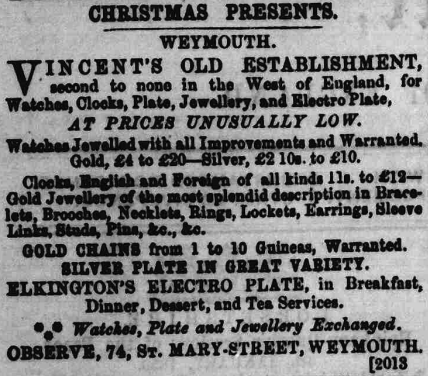

Here in 1862,Vincent’s were advertising their festive gifts for the more wealthy Weymouth residents to purchase for their nearest and dearest.

How about a nice Elkington’s Electro Plated tea service for Mamma? or maybe a set of silver studs for Pappa to wear with his evening attire?

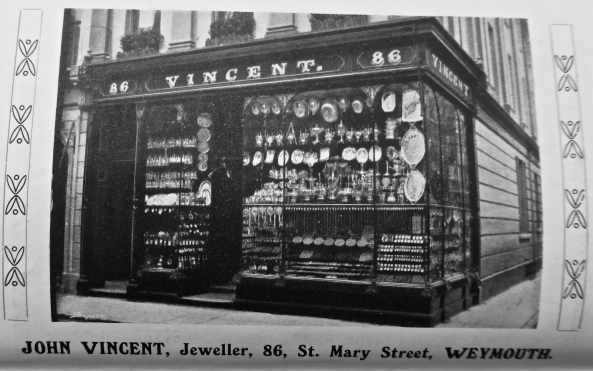

Vincent’s was still an established business even during my lifetime, and it is a shop that I remember well from my childhood.

As a small mite it seemed an imposing sight.

Great tall glass windows outlined by black shiny immaculate wooden frames, enclosed within this imposing outline stood row upon row of glistening silverware, great silver salvers, elaborately carved tea services, jugs and cups. Below paraded the glittering jewels, flashing for all their worth in the suns rays, beckoning beguiled customers to enter their emporium.

Oddly enough, this is also the building where I ended up spending many a happy year working for the fashion retailer Next.

Oddly enough, this is also the building where I ended up spending many a happy year working for the fashion retailer Next.

Victorian Christmas’s did have a slightly different format to our modern day version.

Gifts were given out on Christmas Eve.

This was the day when all the family gathered together to admire the festive tree, (which due to superstition, was not to be put up before Christmas Eve, for fear of invoking bad luck into the family home. )

This green harbinger of festivities was bedecked with it’s precious ornaments and hung with small treats. Strings of popcorn and brightly coloured cranberries draped from it’s fragrant boughs, candle flames flickered and danced in the gloom of the late afternoon giving the room a magical glow.

Crackers would be pulled and children performed.

Christmas day was feasting day, but that was only after the family had attended the church service in the morning. The sound of calling bells rung out across the rooftops of Weymouth, summonsing everyone to service, and the streets were bustling, filled with families adorned in their best finery.

The wealthy and elite of the town jostled with the servants and shop girls, they all had their own paid for places on the hard wooden pews of St Mary’s or Holy Trinity.

The richest were seated in those nearest to the alters and not surprisingly, the poorest at the back.

In those days you paid dearly for the privilege to be nearer to the Almighty.

After filling bellies with fine fares, families would go from house to house, carol singing or packing in more food and drink to their already bursting bellies.

I have just discovered though that for the local shops, Christmas day was just another working day.

That finally explains a scene that I could never understand in Charles Dicken’s Christmas Carol, when Scrooge awoke that cold morning …

“It’s Christmas Day!” said Scrooge to himself. “I haven’t missed it. The Spirits have done it all in one night. They can do anything they like. Of course they can. Of course they can. Hallo, my fine fellow!” “Hallo!” returned the boy. “Do you know the Poulterer’s, in the next street but one, at the corner?” Scrooge inquired. “I should hope I did,” replied the lad. “An intelligent boy!” said Scrooge. “A remarkable boy! Do you know whether they”ve sold the prize Turkey that was hanging up there — Not the little prize Turkey: the big one?” “What, the one as big as me?” returned the boy. “What a delightful boy!” said Scrooge. “It’s a pleasure to talk to him. Yes, my buck.” “It’s hanging there now,” replied the boy. “Is it?” said Scrooge. “Go and buy it.” “Walk-er!” exclaimed the boy. “No, no,” said Scrooge, “I am in earnest. Go and buy it, and tell them to bring it here, that I may give them the direction where to take it. Come back with the man, and I’ll give you a shilling. Come back with him in less than five minutes and I’ll give you half-a-crown.” The boy was off like a shot. He must have had a steady hand at a trigger who could have got a shot off half so fast. “I’ll send it to Bob Cratchit’s!” whispered Scrooge, rubbing his hands, and splitting with a laugh. “He shan’t know who sends it. It’s twice the size of Tiny Tim.”

Of course…even though it was Christmas day, the butcher’s shop was still open for trade.

Boxing day was a day for charity, for giving, to think of those less fortunate. Hence it’s name. Boxes were made up and inside would be coins or small tokens and these would be distributed to shop staff, servants, deliverymen and the poor.

Nowadays, we tend to think more of Boxing day as cold meats, pickles and bubble & squeak followed by a trip to the beach, come rain come shine, to let off steam…well, in our family at least.

But in 1862, and changes were afoot for the hard-working serving members of staff of the local shops.

Boxing day was about to become a holiday.

On the 18th Dec, it was announced in the local papers that “the leading tradesmen in Weymouth have publicly notified their intention of abstaining from business on Friday 26th, the day following Christmas day, in order that their assistants may have an opportunity of visiting their friends.”

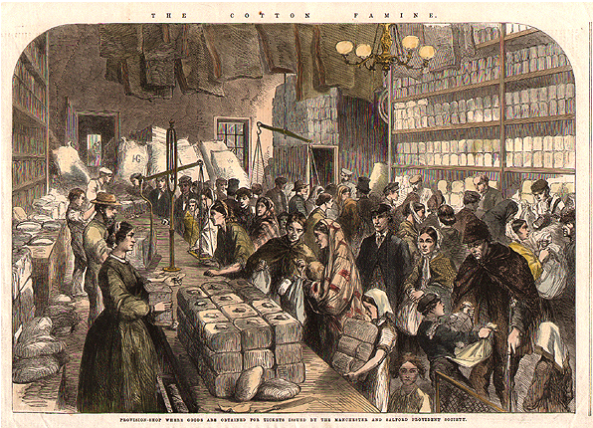

Congregations in all the local churches were kept busy that year, raising funds for their fellow human beings from the north, who at the time were going through devastating changes, often referred to as the Cotton Famine.

A period when the huge cotton mills and associated trades on the northern towns and cities faced a downturn in their fortunes due to world events. Thousands of families suddenly found themselves out of work and facing destitution and starvation.

St John’s collection had raised the grand total of £22 and St Mary’s managed a rousing £17.

Many other events were also being organised in and around the area to help those whose lives had been so harshly turned upside down.

The Manchester Unity of Oddfellows of Weymouth held a well-attended concert at the Assembly Rooms in the Victoria Hotel on the seafront, pictured below.

So too did the local professor of music, Thomas William Beale, he arranged a concert by his friends and acquaintances, which was held a couple of days later, on Christmas Eve.

All funds raised went towards supporting those less fortunate families in dire need.

Despite the overload of bad news we are bombarded with nowadays, it’s heartwarming to see that human nature still favours generosity and the willingness to help those in need at times of crises.

Someone who was very pleased with themselves come that festive period of 1862 was local ship builder and owner, Weymouth born Christopher Besant. At one time they had lived along Hope Quay, near the ship yards where they plied their trade, but had since moved their family to Longhill Cottage in Wyke Regis.

On a chilly Thursday morning just before Christmas, when the tide was at its highest, Christopher, his wife and family strolled down to the harbour, once there they stood excitedly on the quayside.

They were there watching with great pride, the launch of their latest vessel, the 110 ton schooner, Nil Desperandum.

She was destined for trading the foreign coastal routes.

But of course, what would the Christmas period be without at least one little snippet of mischievousness from the locals?

In court that week, stood before the judges, Captain Prowse and Alderman Welsford, were three young lads, aged between seven and nine years of age, frequent offenders it seems and rather unflatteringly referred to as ‘street arabs.’

The trio of troublemakers were there for attempting to fill their own Christmas stockings…by making away with 4 oranges and 3 bread twists, the property of shop keeper Joseph Curtis and his wife Sarah who ran a grocery business in Weymouth High Street.

The ruffian’s parents certainly weren’t described in any more flattering terms than their children by Superintendent Lidbury.

In fact he declared they were ‘worse than the children.’

According to him they had virtually washed their hands of any responsibility, these feisty young lads were running the streets and causing no end of problems all hours of the day and night.

The youngest of the three amigos was 7-year-old Edward Denman, son of recently widowed Ann Maria. Ann Maria tried her best to keep her lively family of six in check, but being a single parent and living in poverty, life was so very hard.

They were all squeezed into the cramped accommodation of no 3 Franchise Court, (which no longer exists,) the entrance to this little court once stood between no’s 5 and 6 Franchise Street.

Sadly, his life lived running virtually unchecked on the streets meant young Edwards career of crime was only to continue.

Come the Christmas of 1865, and he was hauled before the court again, this time for stealing an umbrella and selling it to a local trader, Mrs Russell, who ran, not surprisingly, an umbrella shop in St Thomas Street.

Even though he was only 11 years of age, for this misdemeanor, Edward was sent to prison,

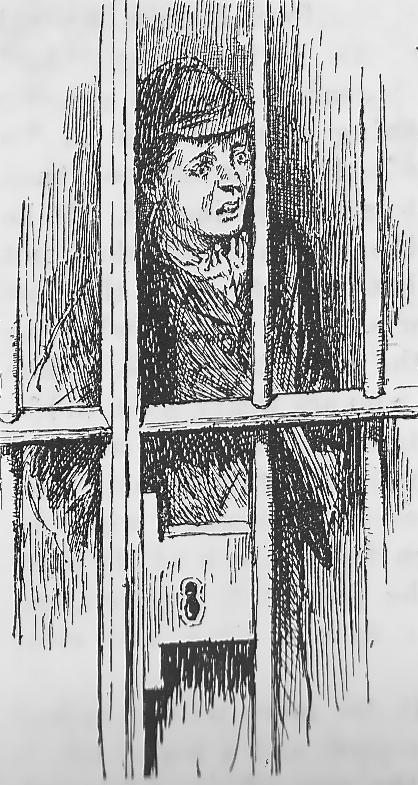

Something that left us a tantalising glimpse of the lad.

The prison admissions book described him as only 4ft 3″ tall, maybe a lifetime of malnutrition might have had that effect?

It goes on to reveal further features of this chappie, light brown hair and hazel eyes, his complexion sallow.

At this tender age, his only distinguishing feature is a cut between his eyebrows.

Once he had completed his hard labour in prison Edward was sent to a reformatory, the Victorian’s attempts at turning such wayward children away from the downward spiral.

By the age of 21, Edward’s life had changed.

Following in his fathers footsteps, he sailed the seas, navigating up and down the south coast on trading vessels.

One thing that hadn’t changed though was his tendency towards being somewhat light fingered.

Before the court again in 1875, this time for the theft of cigars.

Fully grown, he still only measured, 5ft 4 ins.

Now his complexion was described as ‘swarthy,’ a good old fashioned word that exemplified the face of someone who spent their days out in the open fresh air, salt laden winds and fierce sunshine.

His sea faring life was literally tattooed on his body, hearts and daggers on his right arm, his left, an anchor and a cropped sword.

Even his face bore witness to a typical mariners lifestyle, that of drink and frequent brawls, with a “cut right corner left eyebrow” and “cut right corner right eye,” his nose “slightly inclined to right.”

No doubt the lasting legacy of someone else’s fist meeting it.

The second young chap stood before the court that Christmas week of 1862 was 8-year-old Samuel Vincent, son of George and Mary, next door neighbours to his partner in crime, Edward.

Unlike Edward though, Vincent does not seem to have continued on the career criminals pathway, he too followed in his fathers footsteps, working as a sawyer, but then joined the army.

Sadly, though his life was now on the straight and narrow, it was also to be short.

In 1878, aged only 26, he died while stationed in the barracks at Dorchester.

The final fellow felon of our tale is someone that I had come across before, in fact I had already written about him and his brother in my book about the history of the military on the Nothe.

He was the eldest of the three harbourside amigos.

Meet 10-year-old John William Bendall, (though the papers had mistakenly written him down as Benthall, which took some time to decipher who he actually was!)

John lived just around the corner from his accomplices, at no 8 Franchise Street, along with his Dad, Matthew, and Mum, Mary Ann, and the rest of the brood.

John was another one who fell foul of the law more than a few times, despite spending time in prison and the reformatory.

In 1865 he was incarcerated for the theft of zinc.

In 1867, he was arrested for the theft of iron along with his younger brother Albert, this is where I came across this family as the theft was from the Nothe Fort smithy shop.

These slightly over ripe apples hadn’t fallen far from the tree.

Their dad Matthew was no stranger to brushes with the law.

He worked as a waterman, but was also prone to being somewhat light fingered.

Not only that, for some reason he was very unpopular amongst his fellow workers. So much so that in 1888 he even attempted to cut his own throat, part of the reason given was that he was “being so much annoyed by his mates on the quay.”

When these three young ruffians were stood before the court that Christmas week of 1862, they were handed out a present that they didn’t expect, and indeed, wouldn’t forget!

Each and every one of them was flogged…receiving twelve agonising lashes of the whip.

And on that cheery note I wish each and every one of you a very Merry Christmas and a Happy and Healthy New Year.

************************************************

Enjoy reading about the lives of Weymouth and Portland’s residents in the Victorian era?

Why not grab yourself a copy of the book.