Anti-apartheid activist David Motsamayi (not his real name) went 25 years without a flashback to his terrible torture in South Africa. That was until one night last year, when he was chucked into Britain’s most isolated detention centre for migrants. Built on the highest point of the remote Isle of Portland in Dorset, the Verne, which used to be a prison, is surrounded by cliffs and a moat.

As a school kid, Motsamayi survived police bullets in the 1976 Soweto Uprising and graduated to organising clandestine meetings for the ANC. When he was captured, his testicles were electrocuted, his body was battered and his torso badly burned.

“These are the scars of apartheid”, he says, lifting his shirt to reveal the marks on his body. He was held incommunicado for years, at Johannesburg’s notorious John Vorster Square police station. His desperate mother went to mortuaries looking for his corpse. When she was finally reunited with her son, she fainted. “She thought she was seeing a ghost,” Motsamayi said. “She thought I was dead.”

Decades later, he was in trouble again, allegedly facing death threats in South Africa, after investigating the suspicious deaths of his relatives who challenged government corruption. He claimed asylum in the UK and was taken to the Verne.

For the first month, he was in so much shock that he spoke to no one. “All my life I tried to forget the torture,” he said. Now he has flashbacks almost every week. Victims of torture are not meant to be detained, precisely because of the trauma it can trigger, although the Home Office frequently flouts its own rules.

No one knows when any of the Verne’s 580 detainees will be released or deported. Immigration detention in Britain has no time limit, despite repeated criticisms from international organisations including the UN and the Council of Europe. For Motsamayi, “Indefinite detention is exactly the same as what apartheid South Africa was doing. Steve Biko, Nelson Mandela, all our leaders were held indefinitely.”

Motsamayi is not the only one struggling to cope in the Verne. A week ago, a detainee tried to hang himself in the shower. By the time Motsamayi chanced upon him, the man’s eyes were already closed. He raised the alarm and gathered enough inmates to lift the guy’s bodyweight, until guards arrived and cut him down. That man survived, just. Last year, Motsamayi’s friend, Thomas Kirungi, a 30-year-old Ugandan, died at the Verne. Detainees say he took his own life.

Graphic by Georgia Weisz

Figures obtained by VICE reveal that the Verne is the most isolated detention centre in Britain, with at least 80 percent of detainees having no visits from family or friends. That’s assuming nobody visited the same detainee twice, which seems unlikely – meaning even more would have received no visitors at all. Over Christmas, that must have sucked. Motsamayi said the guards gave them crisps and a cola to mark the occasion.

“Levels of anxiety, stress and mental ill-health are high in detention,” said Ali McGinley, director of the Association of Visitors to Immigration Detention(AVID), “and given the complex needs of immigration detainees held at the Verne, it’s a real concern that there is not more support available.”

Detainees in other parts of the country are not quite so isolated. Using freedom of information laws, VICE asked the Home Office how many people visited detention centres, and then compared the data with the number of detainees held at each site. The results showed there were over 63,000 social visits to nine detention centres between July 2014 and June 2015.

However, the statistics reveal an alarming anomaly. Every centre had between one and three visits per detainee per month, apart from the Verne, which had just 0.2 monthly visits per detainee. Are the Verne’s inmates losing a bizarre popularity contest, or is something else going on?

A look at a map shows that the Isle of Portland, where the Verne is located, is connected to mainland England by a narrow windswept causeway, whereas most other detention centres are close to international airports. “AVID is concerned that the location of the Verne disadvantages those held there,” McGinley said. The local Verne Visitors Group explained, “It is virtually on an island. Often detainees ask us where they even are. It’s very expensive to get to from London and other major conurbations, where detainees’ family and friends tend to be, so visiting is difficult.”

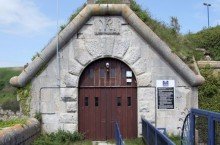

“It was too far for my family in London to visit me, it was horrible,” said Sam Luis, a former Verne detainee from DR Congo. A return train journey from London to Weymouth, the nearest station, costs £63 and takes six hours. Then you have to pay £25 for a cab, or hike up a steep hill. The Verne is inside a Victorian-era fort, entered via a tunnel. The phone signal is patchy at best.

Not everyone who visits a detention centre is seeing family or friends. Some are volunteers from befrienders groups. AVID is an umbrella for 20 visitors groups across the country, numbering nearly 900 volunteers, from students to pensioners. The impact they have on a detainee’s mindset can be the difference between life and death. “A visitor is absolutely critical in terms of helping to alleviate the mental anxiety and distress detainees are faced with,” McGinley said.

Volunteers at the Verne visitor’s group agreed. “People feel extremely isolated. We often find the visiting room nearly empty. Detainees’ mental health is almost always badly affected by detention, but there is no professional counselling available for detainees as far as we know.”

For Motsamayi, it is no accident that detainees at the Verne are massively missing out on a potential lifeline. “The Home Office puts us far away from our families to try to damage us psychologically,” he claimed. And the problem does not stop there. Once detainees are at risk of self-harm, staff at the Verne have an unconventional approach to suicide watch.

When the chief inspector of prisons, Nick Hardwick, inspected the Verne in March last year, he found that, “there was no care suite and detainees requiring constant observations were held in an austere gated cell in the separation unit.” The separation unit “was poor and it was used frequently. Some detainees were held there for several weeks,” he said. Suicidal detainees could only venture outside into an exercise yard that Hardwick described as “stark and cage-like”.

Although his inspection warned months ago that the separation unit was inappropriate for suicide watch, VICE has learned that it is still being used for this purpose. In fact, the man who tried to hang himself last week was not even taken to hospital, but instead placed in the segregation cell.

“If you self-harm, they take you to the block, the isolation unit,” said Luke Simms (not his real name), a gay detainee seeking asylum from a country with extreme homophobic laws.”It’s meant to be for someone who is fighting. But if you are suicidal they just chuck you in the block and they just make it worse.”

Luis, who tried to end his life at the Verne, experienced the segregation unit first-hand. “The block is more depressing,” he explained. “It’s cold, it’s horrible. There is no heating and you have thin blanket.” As a way of preventing suicide, it sounds farcical. “They only check every hour and there is no camera,” Luis claimed.

What Life Is Like as a Night-Shift Worker Looking After Australia’s Incarcerated Aboriginals:

The Verne refused to comment directly. However, in a statement, the Home Office told VICE that: “Detention and removal are essential parts of effective immigration controls. It is vital these are carried out with dignity and respect and we take the welfare of our detainees very seriously.”

“That is why the Home Secretary commissioned an independent review into the policies and operating procedures that have an impact on detainee welfare. Stephen Shaw CBE, the former Prisons and Probation Ombudsman for England and Wales, has completed the review and has recently submitted his report. His findings are being carefully considered.”

“Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons has found the majority of detainees in the Verne feel safe and are very positive about their treatment by staff. A recent report by the Independent Monitoring Board also stated the immigration removal centre is well run and that detainees are treated humanely and fairly.”

The Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123, via email atjo@samaritans.org,or find the details for your local branch can be found atwww.samaritans.org.

This article first appeared Vice magazine

A demo took place in May 2016 outside the Verne and across the country campaigning against the indefinite locking up of people in high security institutions.

Britain is embarrassing itself with this behaviour and those who stand idly by are just as much to blame. Vote and demonstrate for NO More.