Walking up the steps from St Oswald’s Bay you can return to the Coast Path or walk down into Durdle Cove. This is I think the unofficial name, the Ordnance Survey maps do not seem to give it a name!

You are likely to notice the remains of steps down to the beach which were largely destroyed during the wet winters of 2011 and 2012. The steps have been located on the sands and clays of the Wealden Beds which are liable to slumping when wet. It is easy to see why this site was chosen as the slope to the beach is less steep and a shorter distance. However it is more prone to slumping than the Purbeck Beds to the left and the Upper Greensand and Chalk to the right. A new set of steps was constructed for the 2015 summer season allowing a safe if rather a steep descent to the beach.

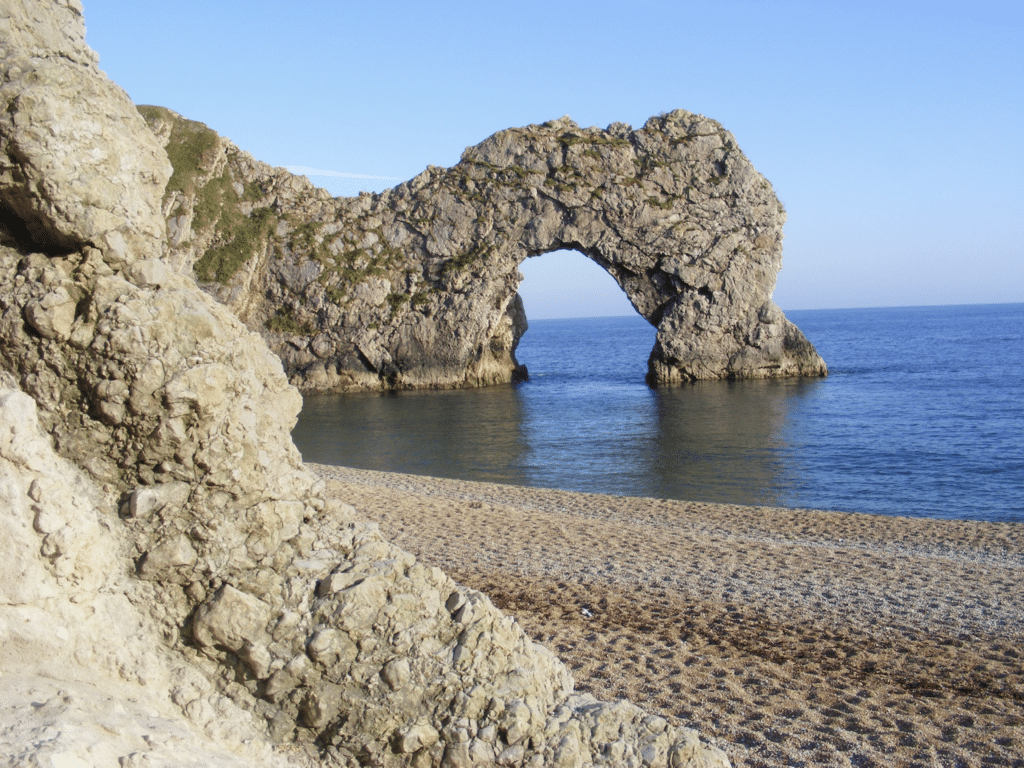

Obviously the main feature in view is Durdle Door, a natural arch formed from the highest beds within the Portland Limestone (seaward side) and the base of the Purbeck Beds (landward side). This is a similar horizon to that seen at the Fossil Forest (article 9) but here the beds of rock are dipping much more steeply (nearly vertical). Careful observation of the north facing surface will show stromatolitic limestone mounds and hollows where fossilised trees could be seen in the past (now removed by collectors). See picture 2 in article 3 for the environmental conditions that helped create these rocks. The arch is probably best seen in the evening light in mid-summer when the north side of the arch is well lit as seen in the picture below.

It is also a good idea to take a boat trip from Lulworth Cove or from Weymouth to see the coastline from the sea.

With a low tide it is possible to see a number of stumps (eroded stacks) of Portland Limestone protruding from the water (the Bull, Blind Cow, Cow and Calf), remnants of the coast from the past. As with Lulworth Cove the sea broke through the Portland Limestone barrier but here the erosion process is much further advanced. At high tide these are likely to be covered with water. The tidal range in this area is up to just over 2m. hence these features may be covered.

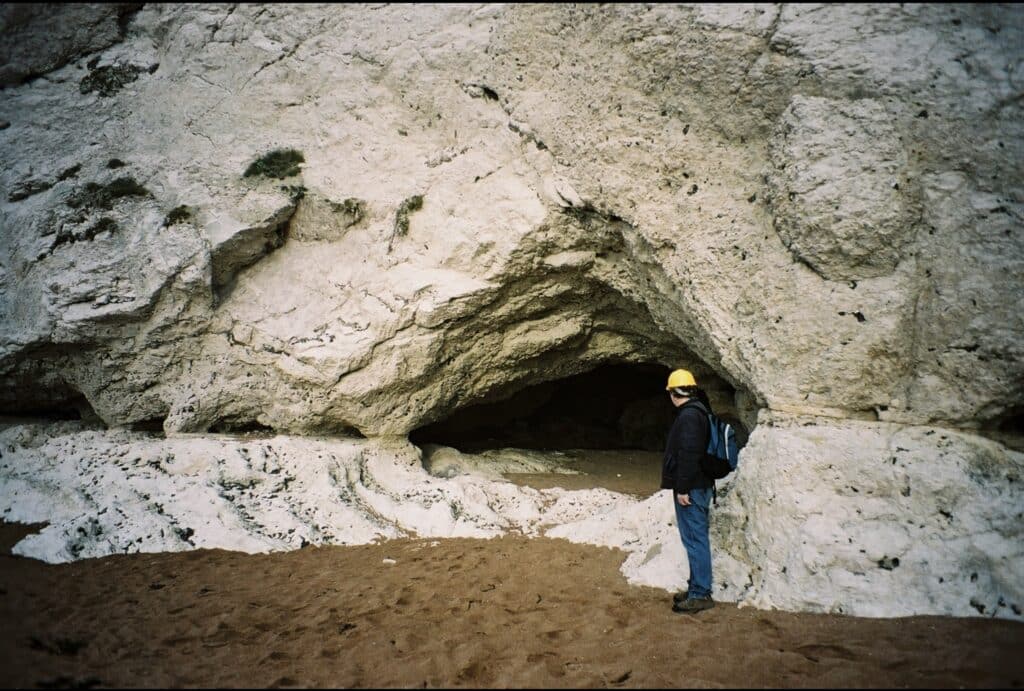

If the tide is low and conditions not too stormy it is worth walking west along the beach from Durdle Door. Rock falls are possible so keep well away from the Chalk cliffs which are nearly vertical. You will see a series of small caves just above beach level and these have been eroded along the line of a fault that runs at a gentle angleinto the cliff.

When the rocks were folded in this area faulting (fracturing) of the rock also occurred. It is possible to see scratches on some of the rock surfaces where one rock has slid over another. These scratches are called slickensides.

If you walk far enough you will reach a valley above the beach called Scratchy Bottom. As mentioned in the previous article this is a dry valley and is partially filled with broken Chalk formed from frost action (freeze thaw) during the cold glacial periods of the Pleistocene (2 million years ago to 10,000 years ago).

The beach beyond Scratchy Bottom has lines of flint nodules running east to west along the wave cut erosion surface. However it may be covered in pebbles. Here the rock layers (strata) are vertical due to the Alpine earth movements mentioned in other articles in this series.

The farthest point on the beach seen in the picture above is Bat’s Head where the vertical dip of the Chalk is apparent and a new arch is being created as erosion of a cave has broken through the headland.

Your journey along the coast continues via the South West Coast Path towards White Nothe.

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/